Less is more — Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

The less boring – Robert Venturi

In a recent article, Alex Tabarrok discussed the problem of modern architecture. Why are architects no longer producing the kind of beautiful old buildings you see in many European cities? Alex cites an article by Samuel Hughes, which rejects a popular explanation: the theory that rich ornamentation is increasingly expensive, especially as there are fewer artisans trained to produce beautiful sculptural details. Hugues shows that this explanation does not hold and that modern technology would make it possible to produce ornaments at a relatively low cost. Instead, he makes a sort of “market failure” argument. Ugly, boring and sterile buildings were imposed on the public by a group of elite intellectuals in the 1920s:

to exaggerate a bit, it actually happened that every government and every business on Earth was convinced by the wild architectural theory of a Swiss watchmaker (Le Corbusier) and a clique of German socialists, so that they began to want something different from what they had sought in all previous eras. It can be said to be mysterious. But the mystery is real, and if we want to understand reality, this is what we must face.

In this article I will argue that there is no market failure. In a certain sense, modernism is what the public really wants. And not just in architecture, but in almost every aspect of life.

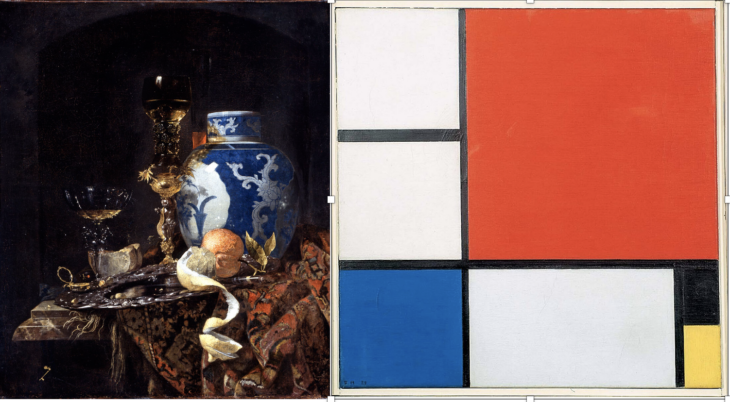

Hughes’ theory is not new. In 1981, Tom Wolfe made a similar argument in From Bauhaus to our house. Unfortunately for Wolfe, the “problem” was not limited to architecture and so he had to write another book (The painted word) explaining why beautiful old styles of realistic painting were being replaced by abstract art. Here are some examples from the Netherlands.

In the case of architecture, tourists generally prefer the more ornate old buildings of Amsterdam to the modernist buildings of Rotterdam, which replaced buildings destroyed during World War II. But buildings aren’t built for tourists, they’re built for residents and workers.

Even two books by TomWolfe are not enough to fully explain modernism, which has touched (infected?) virtually every area of contemporary life. A person with absolutely no training in art theory can immediately recognize the difference between the more complex and ornate traditional styles and the more simple and refined modern styles. So consider how Coca-Cola containers have evolved over time:

Even the name has been simplified: “Coke”. I will show that a similar change has occurred in almost every area of life. But first we need to clarify a few concepts. People often contrast “modern” styles with more “classic” styles. Here, classic means “from the past”. But art historians are more likely to use the term classical to represent a simple, elegant, and symmetrical structure, whereas romanticism represents various forms of complex, asymmetrical, and highly ornate structures.

The British Houses of Parliament were built in the mid-1800s, while the Jefferson Memorial was built in the 1940s. But the Jefferson Memorial is classical while the Houses of Parliament is a form of Romanticism (particularly neo-Gothic ). Indeed, Brazil’s ultra-modern government buildings (see below) are much more “classic” than Pugin’s.th masterpiece of the century.

Tabarrok and Hughes are right: in at least some ways, people prefer more traditional architectural styles. Consider the famous “painted ladies” of San Francisco:

But traditionalists underestimate the extent to which modern styles have impacted even consumers’ residential choices. More than 100 years ago, Frank Lloyd Wright revolutionized architecture by replacing vertically oriented square houses filled with strictly separated rooms with a more fluid horizontal style where public spaces flow seamlessly into one another. Few people are rich enough to afford a masterpiece like this. Martin House in Buffalo, but Wright’s approach influenced the postwar preference for “ranch houses” with large bay windows and open floor plans.

The term “painted ladies” serves as a reminder that modernism also affected women’s fashion. Around 1900, wealthy women wore extremely ornate outfits. By the 1920s (the time of Le Corbusier), women’s fashion had greatly simplified and become more “modern”. In his memoir entitled “The world of yesterday“, Stefan Zweig sees this development as a positive change and relates it to healthy cultural changes that have allowed young men and women to socialize in a more natural and free way. So, old-fashioned corsets and cumbersome dresses were a kind of metaphor for painfully restrictive social mores.

If it’s really true that in architecture, old is beautiful and modern is ugly, why doesn’t this also apply to women’s fashion? Did Le Corbusier also force women to abandon their ornate outfits and replace them with simple black dresses? Certainly, there is a sense in which fin de siècle Parisian fashion was more beautiful than modern clothing. But is this what women want today? I do not think so. They want to be modern. “It’s the style.”

What about cars? Why are people now buying simple, clean styles, and not more ornate styles from the 40s? I suppose one could argue that this partly reflects government fuel economy regulations, but there are too many other examples like this to explain.

I encourage people to go to an antique furniture store and look at all the ornate (and often overly stylish) items on display. You’ll see things like massive oak tables with carved legged legs and heavy dark wood cabinets. Then exit the store and visit a furniture store offering lighter Scandinavian models made from teak wood. The furniture will immediately appear more “modern”. It will also seem more appealing to many people. Did Le Corbusier also impose modern furniture on the public? Was this sleek furniture style imposed by federal regulators? Obviously not. Why did consumers stop buying? ornate silver teapots and move on to sleek modern teapots? Examples of our modern preference for simplicity are almost endless.

The guy who said, “Less is boring” also wrote a book called Learn from Las Vegas. But it’s not one of the lessons of Vegas that it’s not easy to adapt traditional styles to modern needs. Las Vegas is a extraordinarily ugly city. Surprisingly, though, it’s least ugly when it’s at its most modern. The ugliest parts of the Strip are places where traditional styles are clumsily pasted onto monstrous hotels containing 3,000 rooms, while the less objectionable buildings in Las Vegas are a few clean-lined, minimalist modernist towers such as the Hotel Aria. That’s not to say that buildings like the Bellagio aren’t interesting: as a tourist, I’d much rather walk through its lobby than that of a sterile, modern building. But it doesn’t really work as an architecture. It’s way too big for its neo-Italian style.

This is not to say that traditional styles never work. Epic Systems’ headquarters, just outside Madison, is filled with whimsical buildings based on various fairy tales. On the other hand, Apple its headquarters in Silicon Valley is an elegant circle, very much in the style of its consumer products. Aesthetically, the Apple building is more successful. But the Epic campus is probably more fun. To each their own. Companies are incentivized to use architecture that allows them to attract the desired workforce.

I also wouldn’t say that newer is always better. I prefer the best paintings from the years 1600-1670 or 1850-1925 to the best productions of the last 100 years. I prefer mid-century modern architecture to post-modern architecture of the 1970s and 1980s. I prefer pop music from 1965-72 to music from the last 7 years. I prefer films from the 1950s-1980s to those from the last 30 years. Tastes vary and your choices may differ.

But the fact that modernism swept the field in such a wide range of areas suggests that it was not a market failure imposed by elite architects out of touch with reality in the 1920s. is the style that best fits the modern world. And this is true even though most older buildings are, in some sense, “better.” I wouldn’t want Gerhard Richter or Anselm Kiefer to copy the style of Velazquez or Vermeer. I wouldn’t want David Mamet to copy Shakespeare’s style. I wouldn’t want Beyoncé or Taylor Swift to copy the Beatles or Bob Dylan. Each generation tries to find its own style. It’s the job market.