Steve Rosenberg,editor-in-chief of Russia, @BBCSteveR

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRussia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has not only sparked international outrage. It also triggered a wave of sanctions intended to weaken the Kremlin’s ability to wage war against its neighbor.

Russian assets abroad have been frozen, its economy cut off from the global financial system and its energy exports targeted.

I remember Western officials and commentators calling the sanctions “crippling,” “debilitating” and “unprecedented.” With adjectives like these filling the airwaves, the situation seemed clear. The Russian economy would certainly have no chance of withstanding these pressures.

Faced with the prospect of economic collapse, the Kremlin would be forced to back down and withdraw its troops. Is not it ?

Twenty-seven months later, the war rages. Far from being paralyzed, the Russian economy is growing. The International Monetary Fund predicts that Russia will record economic growth of 3.2% this year. Caveats aside, this is still more than in any advanced economy in the world.

The “debilitating” sanctions did not cause shortages in stores. The shelves of Russian supermarkets are full. It is true that rising prices are a problem. And everything that was once on sale is no longer on sale: a number of Western companies have left the Russian market in protest against the invasion of Ukraine.

But many of their products still arrive in Russia through various routes. If you look hard enough, you can still find American cola in Russian stores.

CEOs from Europe and America may no longer flock to Russia’s annual flagship economic event, but organizers of the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum (formerly Russia’s Davos) say delegates more than 130 countries and territories will participate.

Instead of buckling under the weight of Western sanctions, the Russian economy has developed new markets in the East and South.

All this allows Russian officials to boast that attempts to isolate Russia, politically and economically, have not succeeded.

“It seems that the Russian economy has managed to adapt to very unfavorable external conditions,” says Yevgeny Nadorshin, senior economist at PF Capital. “Undoubtedly, the sanctions have seriously disrupted the functioning mechanism of the economy. But many things have been restored. Adaptation is happening.

Workaround

Does this mean the sanctions have failed?

“The big problem was our understanding of what sanctions can and cannot do,” says Elina Ribakova, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

“It’s not like we flip a switch and Russia disappears. What sanctions can do is temporarily unbalance a country until it finds a way around the sanctions, until it finds other ways to move its goods or sell its goods. oil. We are exactly in this area where Russia has found a workaround.”

Moscow has redirected its oil exports from Europe to China and India. In December 2022, G7 and EU leaders introduced a price cap plan aimed at limiting Russia’s revenue from its oil exports, trying to keep them below $60 a barrel. But Western experts recognize that Russia has managed to get around this problem quite easily.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe history of price caps highlights a dilemma for the United States and its partners.

Aware that Russia is one of the main players in the global energy market, they have tried to maintain Russian oil supplies to avoid rising energy prices. The result is that Moscow continues to make money.

“In a way, we refused to properly sanction Russian oil,” concludes Elina Ribakova. “This price cap is an attempt to have the cake and eat it. The priorities are to allow Russian oil into the market and to reduce Russia’s revenues. And when these two priorities conflict, it is unfortunately the first that wins. This allows Russia to generate significant revenue and continue the war.”

Russia has become China’s largest oil supplier. But Beijing’s importance to Moscow extends well beyond energy exports. China has become a lifeline for the Russian economy. Trade between the two countries reached a record $240 billion (£188 billion) last year.

Walk around St. Petersburg or Moscow and you don’t need to be an economic expert to understand how important China has become to sanctions-hit Russia. Electronics stores are full of Chinese tablets, gadgets and cell phones. Chinese car dealerships now dominate the local car market.

The Russian auto industry is not sitting still. At a recent trade show in Nizhny Novgorod, Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin saw the latest version of a classic Russian brand, the Volga. There was only one thing: the new Volga is based on a Chinese car, the Changan.

“Where was this steering wheel made?” Is it Chinese? » asked the Prime Minister, visibly irritated by the lack of Russian components.

“We want (the wheel) to be Russian,” he said.

But ultimately, it’s not the auto industry that’s driving Russia’s economic growth.

That’s what military spending does.

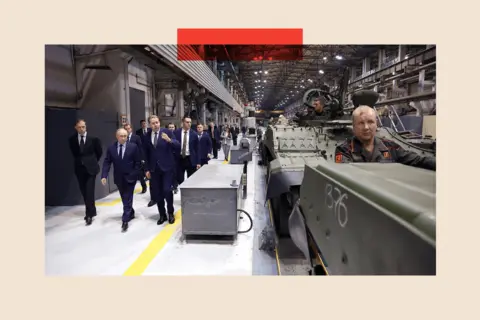

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSince Russia launched what the Kremlin still calls its “special military operation” in Ukraine, arms factories have been operating around the clock and more and more Russians are employed in the defense sector.

This has driven up wages in the military-industrial complex.

But spend big on the military and there’s less to spend on everything else.

“In the longer term, you destroy the economy,” said Chris Weafer, founding partner of the Eurasian consultancy Macro-Advisory. “There is no money for future development.”

He says that in 2020 there were many discussions about the National Project Program, under which $400 billion was to be spent to improve Russia’s infrastructure, transport and communications. Instead, “almost all of this money was diverted to finance the military-industrial complex and support the stability of the economy.”

After more than two years of fighting, the Russian economy has adapted to the pressures of war and sanctions. But the United States is now threatening secondary sanctions against foreign banks that facilitate transactions with Moscow, creating a whole new set of problems for Russia.

“The arrival of products in Russia has slowed down,” explains Chris Weafer. “Spare parts are more difficult to access. Every day, banks in China, Turkey and the Emirates refuse to handle Russian transactions, whether money coming from Russia to buy goods or money returning to Russia to pay for oil or money. other imports. If this problem is not resolved, Russia will experience a financial crisis by the fall.”

This is why it would be wrong to conclude that Russia has circumvented sanctions. So far, he has found ways to manage them, to circumvent them, to reduce the threat they pose.

But the pressure of sanctions on the Russian economy has not disappeared.

BBC in depth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you new perspectives that challenge assumptions, along with in-depth reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll also be showcasing thought-provoking content from BBC Sounds and iPlayer. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking the button below.