Here are five observations on recent trends in Monetary Policy:

1. The Fed would really like to avoid any further interest rate hikes. This psychological aversion to interest rate increases is not rational and actually makes it more likely that the Fed will find it necessary to raise interest rates even further. Indeed, this sort of “reversal aversion” is itself a form of forward guidance, which makes monetary policy more clumsy. This increases the risk that disinflation will reverse, which would require further rate hikes.

2. I’ve seen claims that Jay Powell privately preferred Biden to Trump. People often cite the fact that he refused to cut interest rates as often as Trump would have liked and that he refrained from tightening monetary policy in late 2021 when Biden was considering reappointing him. presidency of the Fed. I don’t know if these accusations of political favoritism are true (I’m skeptical), but if they are true, the implication is that Powell ended up greatly helping Trump and hurting Biden, even though he seemed to be trying to do the opposite.

The message here is clear. People worry a lot about political bias. But when it comes to monetary policy, policy errors are a much bigger problem than policy bias.

3. Mohamed A. El-Erian has a new try in Bloomberg:

Rather than maintaining a policy feedback function rooted in overreliance on retrospective data, the Fed would be well advised to seize this opportunity to undertake an overdue shift toward a more strategic view of the long-term outlook. Such a pivot would recognize that the optimal medium-term inflation level for the United States is closer to 3% and, as such, would give policymakers the flexibility not to overreact to the latest inflation figures. ‘inflation.

As I detailed in a column last month, this trajectory would not imply an explicit and immediate change in the inflation target given the extent to which the Fed has exceeded it over the past three years. Instead, it would be a slow progression. Specifically, the Fed would “first push back expectations on the timing of moving to 2%, then, later, move to a range-based inflation target, say 2 to 3%.” . . .

Although not without risks, such a policy approach would result in better overall outcomes for the economy and financial stability than one where the Fed pursues excessively restrictive monetary policy.

I agree that this would lead to better outcomes for the economy over the coming years. But I don’t think it’s a good idea. Ideally, the Fed would move to a 4% NGDP target. But if they insist on sticking to inflation targeting, they should stay at 2%. This is a classic example of time inconsistency problem. The best policy for the next few years is not always the best long-term strategy. In the long run, there are huge gains from creating a clear rule and sticking to it.

4. Brad Setser expresses some widely held opinions regarding China’s foreign exchange policy:

China must seek policies that bring it closer to internal and external accounting balance – and that means (uncomfortably) limiting the use of traditional monetary policy tools.

But it is also reasonable that China has made real efforts to use its domestic political space to support its own recovery…and so far it has been unwilling to provide direct support to low-income households.or for consider reforms to its exceptionally regressive tax system. Logan Wright and Daniel Rosen stomped on these points in a recent article in Foreign Affairs.

Ultimately, of course, China sets its own exchange rate policy; she has a long history of ignoring outside advice that runs counter to her sense of her own interests. But there is no reason for China’s trading partners to encourage China to move toward more flexibility now, when that would only help it export more of its own manufactured goods to a world reluctant. Pragmatism should prevail.

I have the exact opposite view. China should avoid fiscal stimulus and instead rely on monetary stimulus, even if it results in currency depreciation. I also doubt that this type of yuan depreciation will translate into a larger Chinese trade surplus. Monetary stimulus would likely boost Chinese investment, which tends to reduce its current account surplus. This could also boost domestic savings, but probably to a lesser extent. In other words, the substitution effect resulting from a weaker yen will likely be smaller than the income effect resulting from easy money boosting GDP growth.

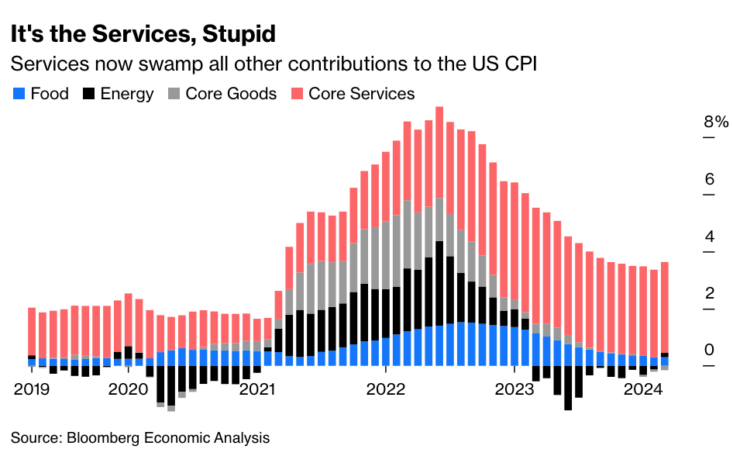

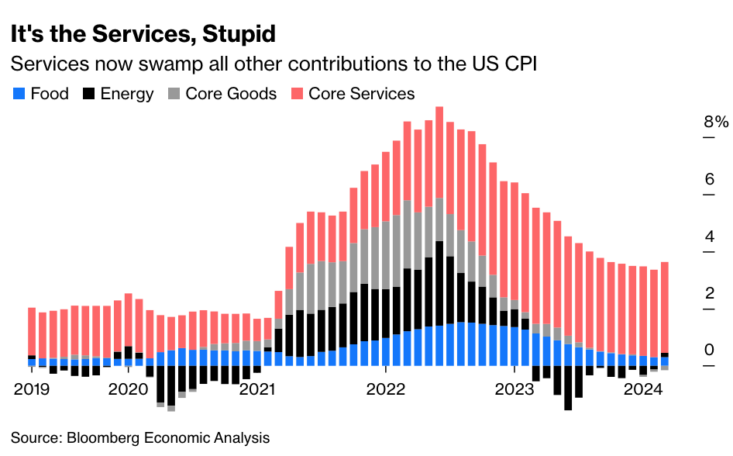

5. John Others at Bloomberg has an interesting chart showing the contribution of 4 key sectors to the overall (12-month) rate of CPI inflation:

Food, energy and basic goods are much more strongly affected by “supply shocks” than services. But monetary policy even has an impact on the prices of these goods. So you can think of the red zone (services) as almost entirely reflecting monetary policy, and the fluctuations in the black, blue and gray zones as reflecting a mix of monetary (demand side) and supply side factors.

Services sector inflation stopped improving after October 2023, which is a worrying trend.