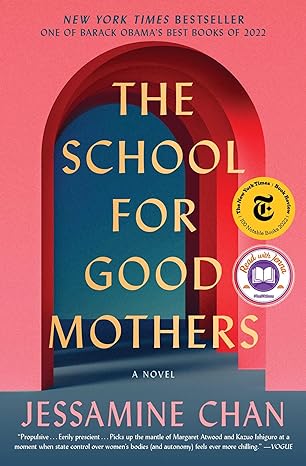

The 2022 novel by Jessamine Chan The school of good mothers (New York: Simon & Schuster) constructs a bureaucratic dystopia in which unfit parents—mostly mothers, but not all—are sent by family courts to a re-education camp run by child protective services. childhood.

Perhaps the scariest part of the story is how easy it is to imagine a path to such a future. After the successful television adaptation of The Handmaid’s Tale debuted in 2017, Margaret Atwood reflects“There is real-life precedent for everything in the book,” she says. “I decided not to put anything in there that someone hasn’t already done somewhere.”

The same can be said of Chan School. Strongly held opinions about the right and wrong way to parent abound in Chan’s world and ours. The same goes for technologies that can monitor all interactions between parent and child. Even scanners and AI technologies capable of perceiving and tracking moment-to-moment moods and micro-reactions seem less like speculative science fiction than products that might appear n any day in a Google ad.

And, of course, we already have a legal apparatus to remove children from unfit parents – and for good reason. Child abuse is all too common and can be incredibly difficult to detect. However, family court and child protection workers, even if well-intentioned, do not always have the ability to know whether they are doing harm or good by removing a child from parental supervision. parents. This is especially evident in the sad cases of children who are unnecessarily removed or subjected to abuse and neglect after being placed in the foster care system. This situation is unfortunately little studiedwith child protection agencies often expected to use limited resources to police themselves.

The main protagonist of Chan’s novel is an overworked, sleep-deprived, recently divorced woman who loses her 18-month-old daughter because she left her house alone in an ExerSaucer for 2.5 hours so she could get coffee and pick up some food. files. his office. Ideal? Certainly not. Maybe not even particularly friendly. But it is far from obvious that this one-off situation is so dangerous that it justifies the trauma of forced removal. It is a situation which reminds THE Living room piece written by the woman who left her children in a car with broken windows on a chilly day for 5 minutes and ended up facing criminal charges that took her years to fight. This particular incident happened to a woman with the skills to write professionally on the subject and the resources to fight the accusations. A report by Human Rights Watch and the ACLU found that children are removed from their homes due to circumstances associated with poverty rather than abuse or neglect, as in the case of the family whose son of eight years was removed because they were use bottled water rather than tap water while temporarily living in an RV until they find a rental. Partly because of higher rates of economic hardship among Black and Indigenous families, they are more likely to be investigated and placed in foster care.

And while I hope I’m right to view forced re-education as something the public would not currently support, it is certainly not without precedent in the United States. The most extreme example is the hundreds of thousands of indigenous children who were kidnapped and forced to be sent to “Indian boarding schools” between the 1860s and 1960s, on the assumption that the state knew what was best for them. The United States already provides resources for home training for people whose children might otherwise be removed. I don’t have any specific arguments to make regarding these programs – I don’t know enough about the details and it’s an empirical question whether or not their current incarnations are useful anyway. But the existence of such a practice suggests that it is not difficult to imagine current policymakers reacting favorably to the idea of putting a parental “expert” in charge of determining whether another parent is doing enough good job. When considering turning to experts, it is always worth it revisiting that of Thomas Leonard Illiberal reformersan incisive history of Progressive Era social reform efforts that compiles example after example of discriminatory and oppressive policies implemented in the name of experts using their supposedly superior knowledge to “correct” the choices of others.

Chan’s novel poignantly illustrates the potential dangers of such a choice. Without spoiling the plot, parents threatened with losing their children are often willing to go to great lengths to prevent this from happening and are therefore vulnerable to abuse and manipulation. The exercise of trying to adapt human relationships to current scientific understanding of what constitutes “best” behavior results in frustrating absurdities. Ultimately, entrusting bureaucratic authorities with discretion over how best to be human robs relationships of their authenticity. In the quest for perfect humanity, we become less human.

Jayme Lemke is a senior fellow and associate director of academic and student programs at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and a senior fellow in the FA Hayek Program for Advanced Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics.