Huda Omari sat outside a broker’s office in Jordan for two days, waiting for her visa to perform the annual hajj, or pilgrimage, to Saudi Arabia.

In Egypt, Magda Moussa’s three sons raised nearly $9,000 to fulfill their dream of accompanying their mother on the pilgrimage to Mecca. When she got the green light for the trip, she says, relatives and neighbors in her village cheered with joy.

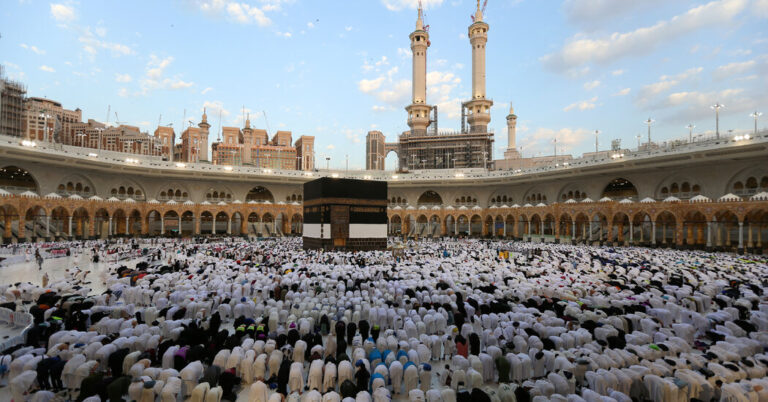

The multi-day pilgrimage is a profound spiritual journey and an arduous trek under the best of circumstances. But this year, amid record heat, at least 1,300 pilgrims did not survive the hajj, and Saudi authorities said more than 80 percent of the dead were pilgrims without permits..

Ms. Omari and Ms. Moussa were among a large number of unregistered pilgrims They both said they were aware that this once-in-a-lifetime trip would be physically and financially taxing, but neither anticipated the terrible heat or the mistreatment they would endure.

“We were humiliated and punished for being there illegally,” Ms. Omari, 51, told The New York Times after returning home.

With nearly two million pilgrims each year, it is not uncommon for pilgrims to die from heat stress, illness or chronic conditions during the Hajj. And it is unclear whether this year’s toll is higher than usual, as Saudi Arabia does not regularly release figures. Last year, 774 pilgrims died from Indonesia In 1985 alone, more than 1,700 people died around the holy sites, most of them from heat stress, A study at the time revealed.

But this year’s deaths have drawn attention to the disturbing underbelly of an industry that profits from pilgrims who often spend years saving to perform one of Islam’s most important rites.

To control the influx of visitors and avoid tragedies like The 2015 stampedeThe Saudi government has attempted to register pilgrims. Those who register must purchase a government-approved travel package, which has become too expensive for many.

Those entering on other types of visas have difficulty accessing the security measures put in place by the authorities. Pilgrims’ financial means therefore determine the conditions and treatment they receive, including their protection from, or exposure to, the increasingly dangerous and extreme heat of the Gulf.

Registered pilgrims are housed in hotels in the holy city of Mecca or in Mina, a white tent city that can accommodate up to three million people and has showers, kitchens and air conditioning. They are also transported from one holy site to another, which protects them from the scorching sun.

Those not registered in Mecca found themselves crammed into empty apartments in a southern neighborhood that has become popular with travel agencies that cater to them, according to some who have been there. During the months surrounding the rite, these agencies rent entire buildings and fill them with pilgrims.

Yet many are not discouraged. And as pilgrims return to their homelands, they begin to get a clearer picture of the conditions they endured.

In collaboration with Saudi authorities, Jordan has limited the number of people allowed to participate in the pilgrimage each year. Jordanian authorities announced last week that they had arrested 54 people and closed three travel agencies after 99 Jordanians died during the pilgrimage.

Ms. Omari lives in Irbid, Jordan’s second-largest city, where she says she sells spices to earn some money. She managed to scrape together 140 Jordanian dinars, or about $200, to obtain a visa that allows Muslims to visit Saudi holy sites but excludes them from the pilgrimage to Mecca.

In total, Ms. Omari paid 2,000 dinars (more than $2,800) for a package that included travel, insurance and accommodation. While not a small sum, she said, it was only half the price of the official pilgrimage package.

Egypt, where inflation and a weak currency make the pilgrimage inaccessible for many, may have recorded one of the highest death tolls this year, but authorities have not confirmed the toll. Egyptian authorities recently shut down 16 tour operators and arrested and charged two travel agents.

Magda Moussa’s three sons had long dreamed of taking her on the pilgrimage, and this year their dream would come true. The trip would cost them 120,000 Egyptian pounds (nearly $2,500) and they would accompany her for 100,000 Egyptian pounds each. The price, however, was much lower than the official package.

When Ms. Moussa, a widowed grandmother who worked as a telecommunications technician, received her visa, her family and neighbors in the village of Bahadah, near the capital Cairo, celebrated her good fortune.

The pilgrimage to Mecca is one of the five pillars of Islam. It dates back to the time when the first pilgrims followed in the footsteps of the prophets. All Muslims who have the physical and financial means are required to perform it at least once.

Today, there are tiered packages for registered visitors and the gap is widening between those who can afford these packages and those who cannot.

Upon arrival, Ms Omari said she was given a room in a building where the air conditioning barely worked.

“It looked like the hallways were on fire,” she said.

So she shelled out more money for a decent hotel, where she shared a room with women from her hometown.

Ms. Moussa was luckier: Her sons paid hundreds of dollars for her to have a bed in a hotel room with three other women, while the sons spent more than $200 to sleep on a mattress on the floor in another building, in a room crowded with eight men.

As the pilgrimage approaches, police raids have intensified, witnesses said.

“We are pilgrims. We are Muslims,” Ms. Omari said. “We are not here to cause trouble.”

Panicked highway agents, fearing arrest, cut off electricity or internet service to some buildings to make them appear unoccupied, witnesses said. Some even chained the doors of buildings to keep pilgrims out and prevent police from entering.

“We often felt imprisoned,” said Ahmed Mamdouh Massoud, one of Ms. Moussa’s sons. He had traveled before as an unregistered pilgrim, he said. But this year, he did not feel welcome.

“I have never seen anything as terrible as this time,” he said, describing the heavy police presence, dozens of checkpoints and random checks.

Ms Moussa said her family lived on canned goods they brought from Egypt during the pilgrimage and, out of fear, only ventured out to buy yoghurt and dates in Mecca.

Ms Omari, who arrived nearly a month before the pilgrimage began in mid-June, remained locked in the room she shared with four other women, leaving only to perform religious rites.

“We know we only go once in our lives, and this was the case this time,” she said.

On the eve of Arafat Day, the day pilgrims gather near Mount Arafat for the pilgrimage, no car or bus would pick her up because she did not have the necessary permit, Omari said. So she walked 20 kilometers to reach the Arafat plain under a blazing sun and stifling humidity. Temperatures exceeded 50 degrees during the pilgrimage period.

“It was like fire falling from the sky and under your feet,” she said.

Ms. Moussa said she tried to board a bus, but a Saudi police officer asked her and the women accompanying her for a permit for the pilgrimage. The officer threatened to end their pilgrimage, so close to its climax, if they could not produce the permit.

“After all these years of waiting for this day, now they want to stop us?” she said.

Ms. Moussa, hurt by the treatment, said she silently exited the bus through the back door. She gathered her belongings and balanced them on her head, then began walking. Stopping only to pray or ask for directions, she walked all night.

“I was wearing plastic slippers,” she said. “When I got there, they were so worn out that I felt like I had nothing on my feet.”

As she walked, she said, pilgrims in air-conditioned buses gaped at her as she limped along the path. Someone took a video of her that went viral in Egypt.

The families of the two women reached the Arafat plain, but the return on foot revealed the tragedy of the situation.

“People younger than me were lying dead,” Ms. Moussa said. “It was heartbreaking.”