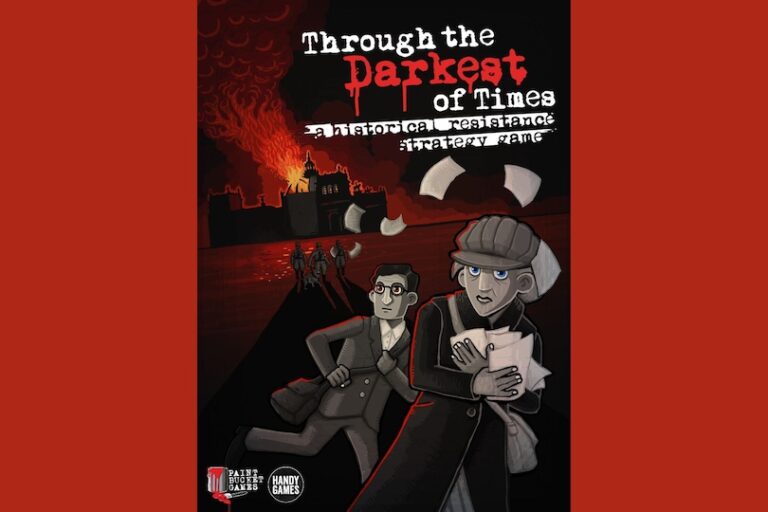

Through the darkest times

Developed by Paintbucket Games, 2020

July 20 this year marks the 80th anniversary of the plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler, carried out primarily by military officers. While resistance efforts such as this and the nonviolent student group White Rose are known to many, other courageous acts of resistance within Nazi Germany remain less well-known. Significant recognition of the German resistance only began in the 1990s, with government commemorations beginning in the early 2000s (Von Lengeling, 2002). memorial ceremony At German Resistance Memorial Center will be attended by officials, including Chancellor Olaf Scholz. This makes the strategy video game, Through the darkest times (TTDT), particularly interesting and timely because it offers a unique role in the commemoration and recognition of the German resistance. It offers an engaging format for understanding the horrors of the Nazi regime, the political changes of the time, and the lives of many opponents of the Nazi regime. Through its immersive narrative, TTDT offers a unique and insightful look at the bravery and complexity of the German resistance efforts.

Players make strategic decisions as the leader of a small resistance group in Berlin. Gameplay alternates between story elements rooted in historical realities and a map of Berlin showing the different missions available each week. These missions range from low-risk actions like buying paper or paint to create and distribute leaflets or writing slogans on walls, to more dangerous tactics like passing on military intelligence, hiding Wehrmacht deserters, or making bombs.

The story spans four chapters and an epilogue and includes weekly newspaper headlines about real events like the Reichstag fire. The first chapter begins with Hitler’s appointment as chancellor in February 1933, covering the rise of pre-war fascism, the consolidation of power through legal means, and the shock and disbelief felt by some. The second chapter is set during the 1936 Berlin Olympics, a platform for Nazi propaganda to reach an international audience. The third chapter is set against the backdrop of the 1941 occupation of France and the invasion of the Soviet Union. If you make it that far, the fourth chapter is set towards the end of the war, and the epilogue follows a year after the war’s end.

The 1930s atmosphere is captured through simple, understated illustrations inspired by 1920s expressionism, with the developers wanting to show what it might have looked like in the 1930s if the Nazis hadn’t banned it (Journal of Geek Studies, 2019). The music shifts from an upbeat cabaret, which you might enjoy for a Giraffe-esque dance, to a dark, tense beat, reinforcing the growing sense of foreboding.

Players must react to events and their effects on the group, such as job losses, coal shortages, or family members joining the Nazi Party, being sent to the front, or being arrested. Increasing the number of sympathizers is essential to expanding the range of missions, and resources such as money, intelligence, and army uniforms may be required. As each week becomes darker and more dangerous, morale inevitably declines, which must be countered by successfully completing missions and making the “right” decisions for the group.

Players begin by selecting a character with a profession, such as welder, judge, or waiter, and a political affiliation opposed to Nazism, including conservative Catholic, moderate liberal, social democrat, communist, and anarchist. Two random members are added to the party, with the option to recruit more from a selection. Each character has skills in Propaganda, Empathy, Secrecy, Strength, and Literacy, which are better suited to certain missions. A communist with a Propaganda skill might excel at talking to workers or soliciting donations in the working-class district of Kreuzberg, but might have difficulty connecting with a priest or obtaining donations in the more conservative district of Wedding.

The developers were inspired by several resistance groups, including one led by Harro Schulze-Boysen and Arvid Harnack (Journal of Geek Studies, 2019), who worked for the Reich administration and passed information to the Soviet Union. Another, the Baum Groupwas composed primarily of young Jewish communist sympathizers. A German social movement of resistance to Hitler never emerged. Instead, individuals acted alone, and groups were typically small, disparate, and often unaware of each other’s existence (Von Langeling, 2002). Forming a politically diverse group within the TTDT may be advantageous, although it perhaps conveys a sense of solidarity and diversity that was less common within resistance groups, which often coalesced around common political orientations. This was recognized to some extent by the potential for internal conflict that you would have to resolve.

Historians have debated the extent to which the German population was powerless to resist in such a repressive environment, where simply speaking out was considered treason and thousands of opposition members were arrested. While it may seem that resistance was nearly impossible, some have suggested that a myth of the Nazi terrorist state emerged to explain the perceived passivity of the population, but the population did resist or could have resisted more actively, particularly those groups that were not directly targeted by the Nazis (see Johnson, 1999; Kershaw, 1999; Wolfgram, 2006). This tension is reflected in the game through the difficulty of completing missions and the fluctuating levels of risk, as certain areas of Berlin or certain members of the group are subject to increased surveillance, which can result in injury, arrest, and even torture. Significantly, though, TTDT shows that there was also hope and solidarity – you could attend a mass protest (before they were banned), support other members, receive help from strangers, and get encouraging news from journalists and resistance efforts outside the country. Ultimately, the game depicts individuals willing to take risks and some successful acts of resistance, albeit in limited forms.

Unlike many video games where the mission is to take down Nazis without question, TTDT’s strength lies in demonstrating the impact of the regime on daily life, the politicization of everyday activities, and the importance of individual, everyday acts of resistance. Although character development is limited, aside from the main story told primarily by the group leader and occasional news or opinions from other members, the game elicits a strong emotional response. The sense of fear, sadness, guilt, and helplessness is palpable when witnessing abuse or learning about concentration camps and atrocities on the Eastern Front. Would you intervene when an elderly Jewish man is about to be beaten by the SA, or would you cross the line of brownshirts in front of a store holding signs that read “Don’t Buy From Jews!”? Or would you ignore it, fearing it would be too risky and draw attention to your group? The game effectively captures the moral dilemmas and emotional weight of resistance, making it a powerful and thought-provoking experience.

As with other narrative games, some of TTDT’s decisions can feel somewhat redundant and inconsequential, but most of them advance the story and keep you immersed in it. There is no significant overlap between story and mission elements, though new missions may become available based on your curiosity and exploration of the story. Despite the complexity of the problems presented, the simple mechanics on the mission side can start to feel repetitive. At the start of each chapter, many elements are reset, and missions and their impact are once again limited as you work to rebuild supporters and morale. Larger, riskier missions that appear later require multiple elements to align, such as critical intelligence, multiple army uniforms, explosives, or a truck, making them nearly impossible to complete in the 20 turns available per chapter. While potentially frustrating to play, this reflects the real difficulties and futility faced by those attempting such tactics. Likely, like the people involved, you begin to wonder if the risks are worth it and if your actions will make a difference. Although you know that the resistance in Germany failed to stop Hitler’s regime, the game encourages you to take action, no matter how small.

TTDT’s message is clear, and the developers are quick to draw parallels with current politics. The rise of fascism in Europe, particularly Germany, and the United States motivated them to create a game with an anti-fascist message and to demonstrate that “history is not only changed by generals and leaders, but by all of us” (Journal of Geek Studies, 2019, p. 54). While TTDT is not fun in the traditional sense, it is an enjoyable and engaging way to understand how and why people resisted (or why they didn’t) and the complex factors that influence those decisions. It provides an excellent platform to learn and teach about this period of history, the overlooked aspects of resistance to the Nazis, and resistance to oppressive regimes in general.

The references

Johnson, Eric (1999) Nazi Terror: The Gestapo, the Hews, and Ordinary Germans Basic books.

Journal of Geek Studies (2019) “Through the Darkest Times: Resistance Life in the Third Reich,” Geek Studies Journal, 6(1), 49-54.

Kershaw, Ian (1999) Popular Opinion and Political Dissent in the Third Reich: Bavaria, 1933-1945, Clarendon Press.

Von Lengeling, Volkher (2002) “The Moral Example of the German Resistance Against the Nazi Regime”, Journal of human values, 38(3), 234-246.

Wolfgram, Mark (2006) “Rediscovering German Resistance Stories: Opposing the Nazi “Terrorist State”.” Rethinking history, 10(2), 201-219.

Further reading on electronic international relations