This is Yves. Wolf Richter explains why revisions to unemployment statistics don’t seem untoward or suspicious, but how the hyped reports are blatantly bad and agenda-driven. Which does not mean that choosing the Fed as inflation firefighter by default is a good idea.

By Wolf Richter, editor-in-chief of Wolf Street. Originally published on Wolf Street

Our favorite recession indicator shows that the next recession continues to recede.

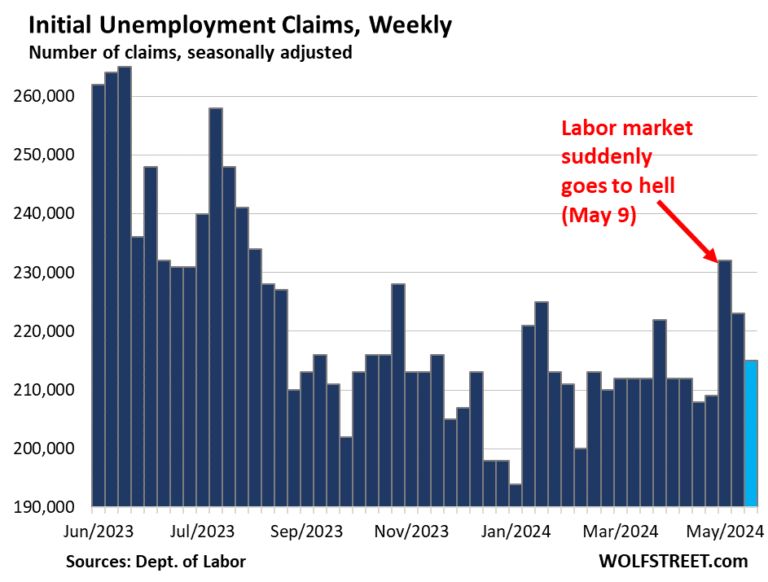

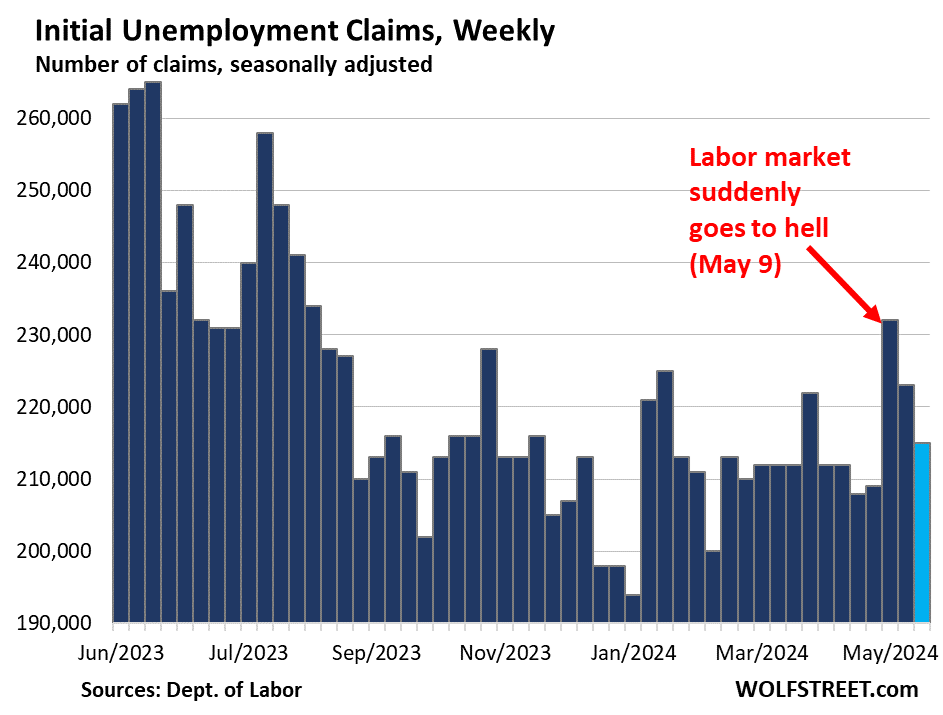

It’s rather funny. Initial claims for unemployment insurance fell by 8,000 to 215,000 in the current reporting week, after falling by 9,000 the previous week, according to Labor Department data this morning.

What’s funny is the media treatment of the 232,000 jump two weeks ago (May 9): it was presented as a sign that the labor market was suddenly weakening and that the Fed would soon start to reduce its rates (which we obviously pooped at the time).

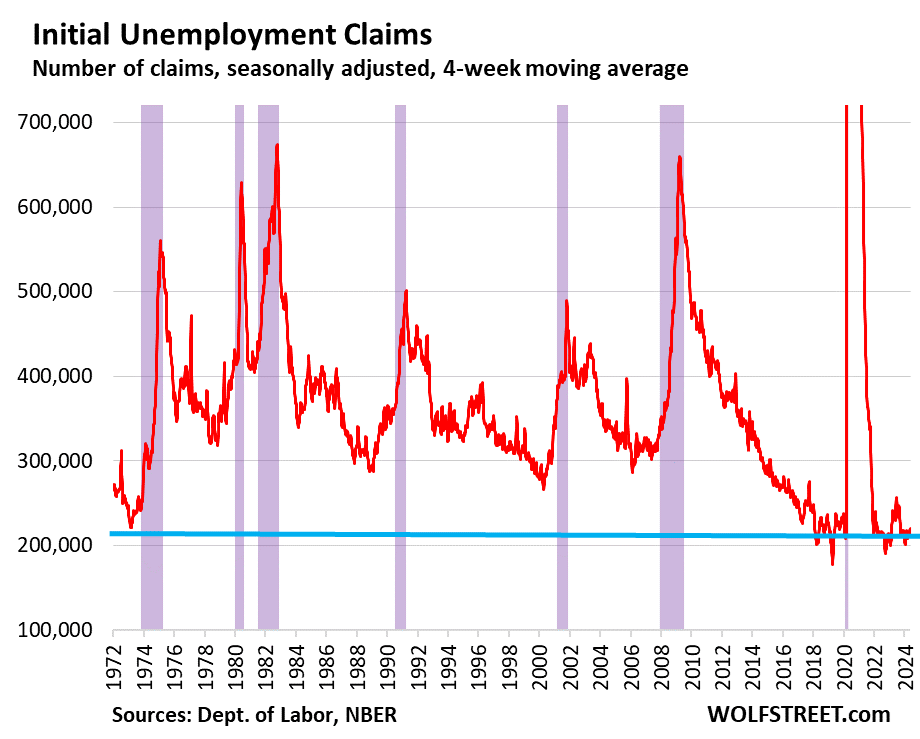

So today, initial unemployment claims have returned to the historically low levels that prevailed for much of the past two years, another sign that the labor market is relatively tight. We take this seriously because the data is part of our favorite recession indicator (more in a moment):

One of the main reasons this initial unemployment claims data varies so much from week to week is that it is raw data on unemployment insurance claims that newly laid off people filed to State agencies, and which State agencies then process and submit on a weekly basis. deadline to the Ministry of Labor.

One of the main reasons this initial unemployment claims data varies so much from week to week is that it is raw data on unemployment insurance claims that newly laid off people filed to State agencies, and which State agencies then process and submit on a weekly basis. deadline to the Ministry of Labor.

When they miss the deadline, these claims are carried over to the following week, reducing the number of claims in the current week and increasing the number of claims in the following week. When Rhode Island does it, no one notices the difference. But when one of the big states does it, it causes big changes from week to week.

This is precisely why the Department of Labor also publishes the four-week moving average, which smooths out these shifts between weeks.

On May 9, the four-week rolling average of initial claims rose to 215,000, after remaining essentially flat at historic lows, as shown we pointed this out at the time.

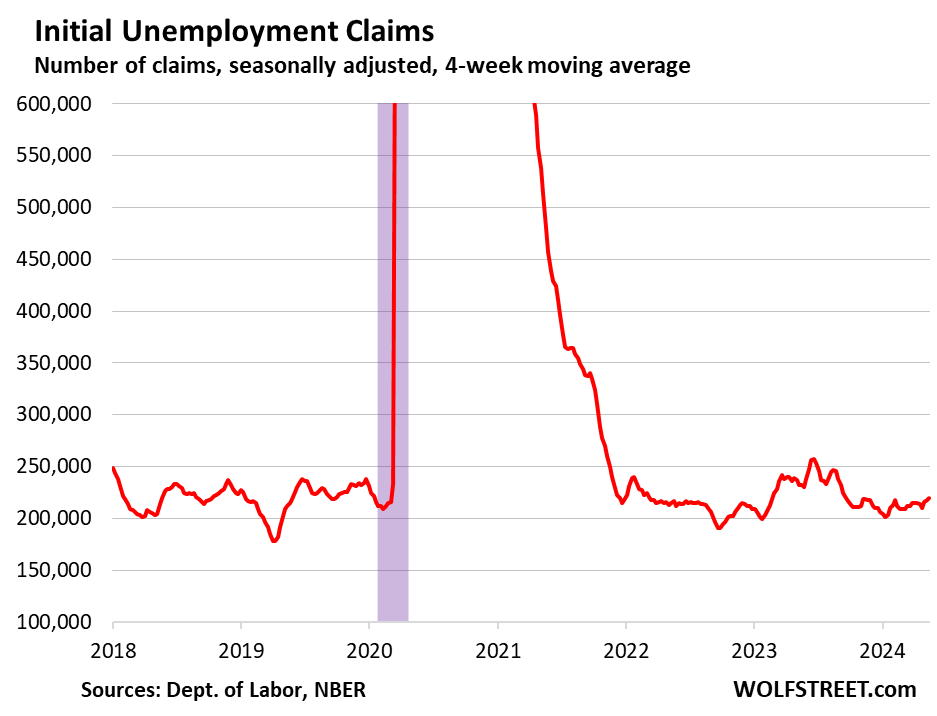

Today, the four-week moving average rose to 219,750, still at historic lows. The small bump now gone between February 2023 and September 2023 was the result of layoffs in the tech and social media sector:

The long-term view (recessions marked in purple) shows how historically low these initial unemployment insurance claims are, especially considering that employment and the labor force have grown over these decades, while like the population:

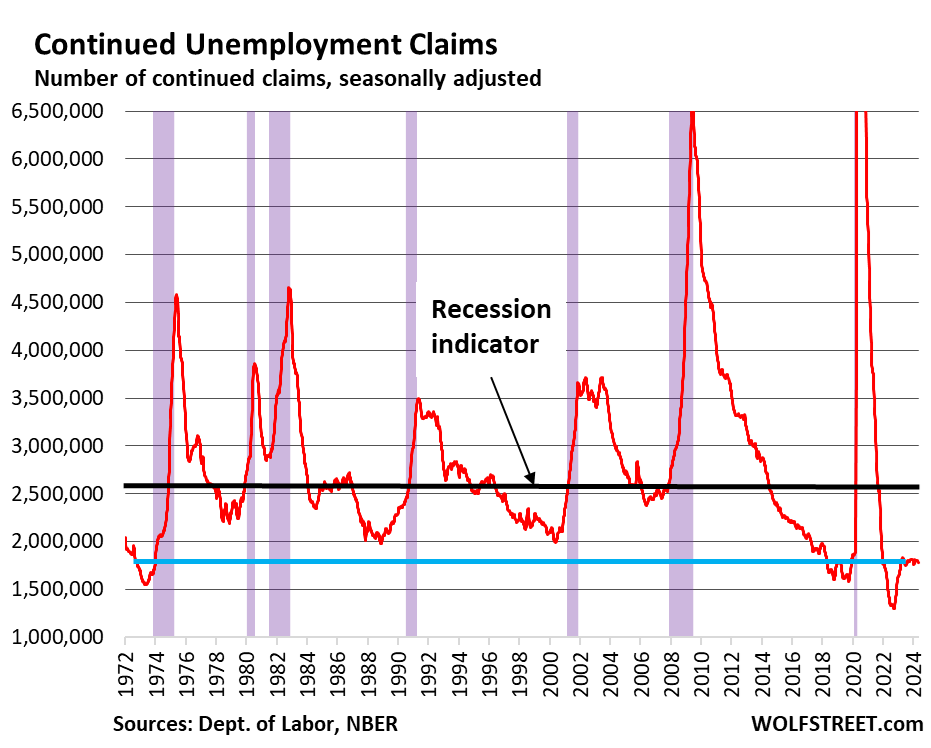

Our favorite recession indicator

We are on recession watch shortly after the Fed launched its rate hikes in March 2022. The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), which denounces American recessions, has always defined them as broad economic downturns including downturns. of the labor market.

We therefore expect large increases in weekly unemployment claims (charts above) and large increases in continuing unemployment insurance claims (charts below).

The number of people still claiming unemployment insurance benefits at least a week after first applying – people who have not yet found a job – has been at the same relatively low level since mid-2023.

During the current reference week, 1.79 million people were still using unemployment insurance. The four-week moving average remained roughly stable around 1.78, and down slightly from December levels of 1.81 million.

A higher level of continuing claims suggests that it takes on average slightly longer for people who have lost their jobs to find a new job.

This “frying pan” pattern, as we have come to call it, has appeared in much economic data, formed by undershooting in the wake of the pandemic and then a return to normalization:

Our indicator (below) indicates an impending recession when the blue line approaches the black line

Recessions from the Great Recession through the early 1980s began when continuing unemployment insurance claims exceeded the 2.6 million mark (black line in chart below).

The current level of 1.79 million (blue line) is well below recession levels (black line). It highlights one of the tightest labor markets in the last 50 years and tells us that there is still no recession in sight.