From Sarajevo in 1914 to Munich in 1938, historical analogies provide a cognitive shortcut to help us make sense of complex issues, allowing policymakers to make decisions with a minimum of original analysis. In no area is this trend more visible than in the study of China-US relations, where a rotating group of scholars have sought to understand and shape the world’s most important bilateral relationship by looking back to the past. But in most cases, direct—and overwhelmingly Western-oriented—historical analogies have proven more likely to obscure and confuse than to illuminate and guide assessments of U.S. relations. China. Even more worrying, given that the most common analogies are drawn from past wars, their irresistible appeal risks creating a self-fulfilling dynamic that draws countries closer to conflict.

Graham Allison’s popularization of the “Thucydides trap” frames the relationship between the United States and China using the timeless dynamic of a rising power (China) threatening an established power (the United States). Just as Sparta’s fear of the rise of Athens made the Peloponnesian Wars “inevitable,” Allison argues that China’s emergence as an economic and military rival to American hegemony will push the two countries toward a violent confrontation. This framework has proven deeply influential in foreign policy circles, with Joe Biden describing Allison as “one of the most fervent observers of international affairs» and Xi Jinping repeatedly citing the need to avoid Thucydides’ trap.

The ubiquity of Allison’s theory among practitioners, however, was offset by the zeal with which his colleagues attacked both the concept of the Thucydides Trap and its application to Sino-American relations. While classical scholars claim that the framework arises from a misreading the history of the Peloponneseother commentators have challenged its underlying causal mechanism, arguing that aspiring powers, rather than established ones, are more likely to start war. Other critics argue that the “Thucydidian cliché” overestimates Chinese strengthwhile downplaying the geopolitical importance of China-US economic interdependence and the strength of America’s regional allies. Strategic hawks in the United States also joined the chorus of disapproval by rejecting Allison’s recommendation to “accommodate” China, arguing that his aggressive stance was not motivated by political will. An authoritarian but distracted United States.

Allison is far from alone in seeking to bend history to fit China-US relations (and vice versa). Drawing on the same theory of hegemonic war, many commentators have made disturbing comparisons between U.S.-Chinese relations and Anglo-German competition before 1914. Like modern China, Imperial Germany was an ascendant “revisionist power” that was rapidly expanding its navy to challenge its established rival for regional dominance. In this light, Sino-American economic interdependence serves less as a hedge against future conflict than as another strange similarity to pre-1914 Europe. But ignoring Russia’s role in driving Germany towards war, this analogy misses the importance of war. The Chinese geostrategic context, less perilous, which protects it from any realistic threat of invasion. Furthermore, the Anglo-German analogy neglects the role of nuclear deterrence in contemporary international relations and underestimates the historical contingency of Europe’s “nuclear deterrence.”somnambulism» at war in July 1914.

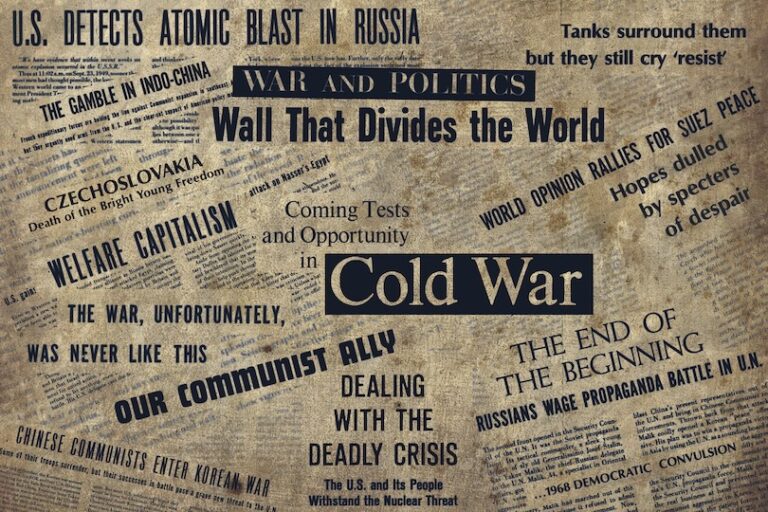

The recent deterioration of relations between the United States and China has also witnessed a proliferation of “Cold War” analogies in which China replaces the USSR as the principal ideological and geopolitical antagonist of the United States. But while reflecting a the long-standing Chinese desire to learn from the mistakes of the Soviet Union, this analogy also fails to account for the contemporary relationship between the two states. Certainly, China’s authoritarian state capitalism’s challenge to Washington’s liberal-democratic model superficially mimics the ideological clash between America and the USSR, but China lacks the universalist ideology that shaped the dynamics of the Cold War. The depth of cultural and economic ties between America and China is also very different from the bifurcated structure of Cold War relations, and even despite the growth of their “limitless partnership“Along with Russia, China does not have the Soviet system of international alliances. Crucially, the Cold War analogy can also lead to a cognitive bias which overestimates the malicious intentions of each party and misdiagnoses “security-seeking” behavior as “power-seeking” ambition.

Should we then abandon the comparisons and declare that the relationship between the United States and China is unprecedented? Certainly, the sense of uniqueness is reflected in each country’s assertions of its own exceptional character. Although the re-emergence under Trump of an “America First” ideology explicitly challenges notions of America’s “civilizing mission,” America’s status as a “civilizing mission”extraordinary nation” with a “special role to play in the history of humanity”” continue to invade foreign policy under Biden. At the same time, China’s evolving but persistent sense of its own superiority – based on a sense of its historical destiny as a great power – dominates Xi’s approach to international relations. There is also a sense on both sides of the Pacific that the quantitative scale of Sino-American global domination is qualitatively unique. The United States and China matter together 43% of total global GDP And more than half of the world’s military personnel expensesand their collective contribution to Co2 emissions far exceeds their closest rivals. But a bilateral relationship cannot defy comparison simply because its protagonists consider themselves unique, or because they hold unprecedented resources. In fact, historical analogies persist even among those who hail the distinctiveness of the U.S.-China relationship. Niall Ferguson’s illusion of a “Chimerical“of codependence between countries, for example, implicitly invokes Nichibei, which encourages American fears of Japanese ascendancy in the 1980s.

If the seductive nature of analogies for US-China relations cannot be overcome, they can at least be improved on three points. First, US-Chinese commentators should rely on a broader repertoire of analogies to avoid cognitive biases. They may want to ask themselves, for example, whether Anglo-French naval diffusion during the 19th century is a better comparison than the Anglo-German arms race, or whether the Cold War analogy works better with America refounded in the role of the Soviet Union. Second, analogies should focus less on the protagonists of the past than on the underlying mechanisms that led to historical change. As Ian Chong and Todd Hall noticeFor example, 1914 provides useful lessons about the dangers of complex alliance systems, rising nationalism, and persistent crises, without requiring a direct comparison between Imperial Germany and China. Finally, in drawing analogies, commentators should avoid the unfounded but persistent assumption that Europe’s past will be Asia’s futureand search for precedents from the entire Asia-Pacific region itself. The results might sell fewer books, but could slow the march toward war.

Further reading on international electronic relations