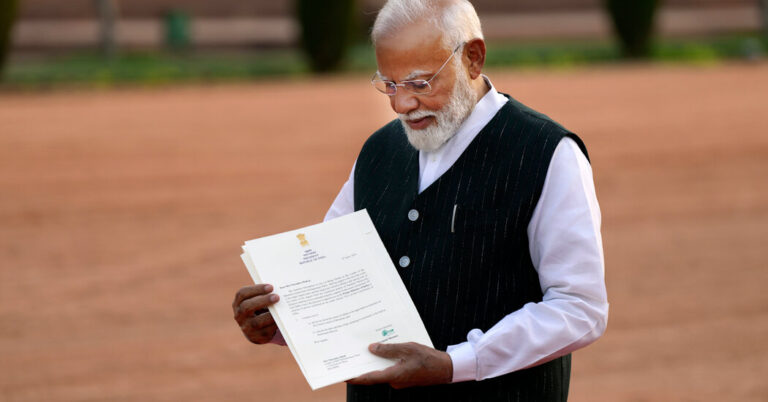

As a humbled Narendra Modi prepared on Sunday to be sworn in for a third term as India’s prime minister, the political air in New Delhi seemed transformed.

The elections that ended last week stripped Mr. Modi of his parliamentary majority and forced him to turn to a diverse set of coalition partners to stay in power. Today, these other parties are enjoying something that for years belonged singularly to Mr. Modi: relevance and attention.

Their leaders were invaded by television crews as they prepared to present their demands and political opinions to Mr. Modi. His opponents also benefited from more airtime, with channels cutting their press conferences live, which is almost unheard of in recent years.

Above all, the change is visible in Mr. Modi himself. For now, at least, the messianic air is gone. He presents himself as the modest administrator that voters have shown they want.

“To run the government, you need a majority. But to lead the nation, consensus is necessary,” Mr. Modi said in a speech to members of his coalition on Friday. “People want us to do better than before. »

For many, Mr. Modi’s change in approach can only mean good things for the country’s democracy – a move toward moderation in a wildly diverse nation that was becoming a Hindu monolith in the image of just one man.

The question is whether Mr. Modi can truly become what he has not been during his two decades in elected office: a consensus builder.

A new man, or at least a new way

“He is a pragmatic politician and, for his own survival and that of his party, he will be softened a bit,” said Ashutosh, a New Delhi-based analyst who uses only one name and is l author of a book on how Indian politics has changed under Mr. Modi. “But to assume a qualitative change in his style of governance is to expect too much.”

One of the hallmarks of Mr. Modi’s rule in recent years has been the use of the levers of power at his disposal – from the pressure of police affairs to the lure of a share of power and its benefits – to break his opponents and get them to side with him. . A battered ruling party could well resort to such tactics to alienate some lawmakers from its camp, analysts say, in order to strengthen its place at the top.

But in the days leading up to the swearing-in, a change in approach was evident. When members of the new coalition gathered in the hall of India’s old Parliament on Friday to deliberate on the formation of the government, every time a senior ally sitting next to him stood up to begin his speech, Mr . Modi also stood up. When it was time for Mr. Modi to be introduced as the coalition’s chosen prime minister, he waited the leaders of the two main coalition partners to arrive at her side before the congratulatory wreath of purple orchids was placed around her neck.

His hour-long speech contained none of his usual third-person references to himself. His tone was measured. He focused on the coalition’s promise of “good governance” and “the dream of a developed India”, and he acknowledged that things would be different from the last ten years.

The last time Mr. Modi came to the Parliament complex for a well-attended event last May, he inaugurated In a new, more modern building for the assembly, he made an entrance that some observers compared to that of a king: with marks on his forehead as a sign of piety and a scepter in his hand, while Hindu monks shirtless, singing, walked in front and behind him.

This time, he turned directly to a copy of the Constitution, which declares India to be a secular, socialist democracy, bowing before it and raising it to his forehead.

A return to debate and parliamentary procedures

For the first time in more than two decades in power, Mr. Modi finds himself in uncharted territory. So far, as long as he has been at the helm of the country – whether at the state level as Gujarat chief minister or at the national level – his Bharatiya Janata Party has always had a majority. Analysts say his history of never being in opposition has shaped his authoritarian approach to politics.

When he left Gujarat, after 13 years, he had established such a firm hold and so routed the opposition that the state had effectively become a one-party government. His first national victory in 2014, with a majority for his BJP, ended decades of coalition government in India, during which no party had managed to win the 272 seats in Parliament needed for a majority. In 2019, he was re-elected with an even larger majority.

Mr. Modi’s enormous power made it possible to quickly implement what had been his right-wing party’s decades-long agenda, including construction of a sumptuous Hindu temple on a long-disputed site that once housed a mosque, and the revocation of the special status long enjoyed by the Muslim-majority region of Kashmir.

A mark of his governance was his disregard for parliamentary procedures and legislative debates. Its unexpected and sudden demonetization in 2016 – which invalidated India’s currency in a bid to combat corruption – plunged the country into chaos and dealt a blow to a still cash-driven economy. Likewise, the rush to enact laws to restructure the agricultural market resulted in a year of demonstrations which suffocated Delhi, forcing Mr. Modi withdraw.

Before the election results were released, Mr. Modi’s party predicted that his coalition would win 400 seats in the 543-seat Indian Parliament. The opposition would be reduced to sitting “in the spectators’ gallery”, Mr Modi said. His government officials had made it clear that during his new term, he would seek to implement the one main item remaining on his party’s agenda: legislating a “uniform civil code” in this diverse country to replace the different laws of different religions that currently govern issues such as marriage and inheritance. His party leaders have spoken of Mr. Modi not only as their leader for the current term, but also for the next elections in 2029, when he will be 78 years old.

“He tried to transform the country,” Sudesh Verma, a BJP official who wrote a book about Mr. Modi’s rise, said in an interview before the election results were announced. “I look forward to seeing him work like Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew, who worked until he was 90.

But under a coalition government, Mr Modi’s traditional approach will be difficult.

Two of the main coalition parties who helped him secure the minimum number of seats in Parliament to form a government are secular, contrary to Mr. Modi’s Hindu nationalist ideology.

N. Chandrababu Naidu, whose party holds 16 seats, has been scathing in the past in his criticism of Mr. Modi’s treatment of the Muslim minority. He also openly criticized Mr Modi for using central investigative agencies to target his opponents and taking “steps aimed at subverting all democratic institutions”.

Neerja Chowdhury, a Delhi-based political analyst and author of the 2023 book “How Prime Ministers Decide,” said: “Controversial ideological issues, like the enactment of a uniform civil code, could be put on the back burner if allies are ready to do it. not comfortable with that.

Mr. Modi’s popular image rests on two solid pillars. He is a champion of economic development, with an inspiring biography about rising from humble caste and relative poverty. He is also a longtime Hindu nationalist, with decades as a foot soldier in a movement seeking to make India’s secular and diverse state an openly Hindu place.

At the height of its power, the Hindu nationalist aspect increasingly dominated. Analysts say the recent voter rebuke could be a stroke of luck for the nation: prompting Mr. Modi to harness his development-champion side and focus on a legacy of economic transformation that could improve the lives of all Indians.

Suhasini Raj contributed reports