Last week’s issue of The Economist has published a few articles on disinformation, which it defines as “lies intended to deceive.” More specifically, I would define it as the intentional publication or dissemination of factual information that is almost certainly false by a person or organization whose interest is in spreading the lie.

The article “The Truth/Lies Behind Olena Zelenska’s $1.1 Million Cartier» (“Anatomy of Disinformation” is the title of the shortest printed version) details a recent case. Researchers at Clemson University have retraced, step by step, the story of how Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s wife allegedly spent $1.1 million on Fifth Avenue in New York. The fake story, recycled from an earlier one, went from an Instagram video (presumably from someone in St. Petersburg) reposted on YouTube to African news sites often repeating it as “promoted content” ( i.e. a paid promotion). to Russian media, to a fake American publication called DC weekly, and its republication as credible information. Ultimately, it was shared at least 20,000 times on Twitter and TikTok. Many people now think this is proven old “news”.

This sophisticated example of disinformation was almost certainly a Russian government operation. Such operations carried out by foreign governments are particularly difficult to uncover: no journalist can seek out and interview the woman in St. Petersburg who allegedly launched the lie on Instagram. In a freer country, the free press can more easily uncover and publicize government disinformation conspiracies, making such operations riskier and less likely.

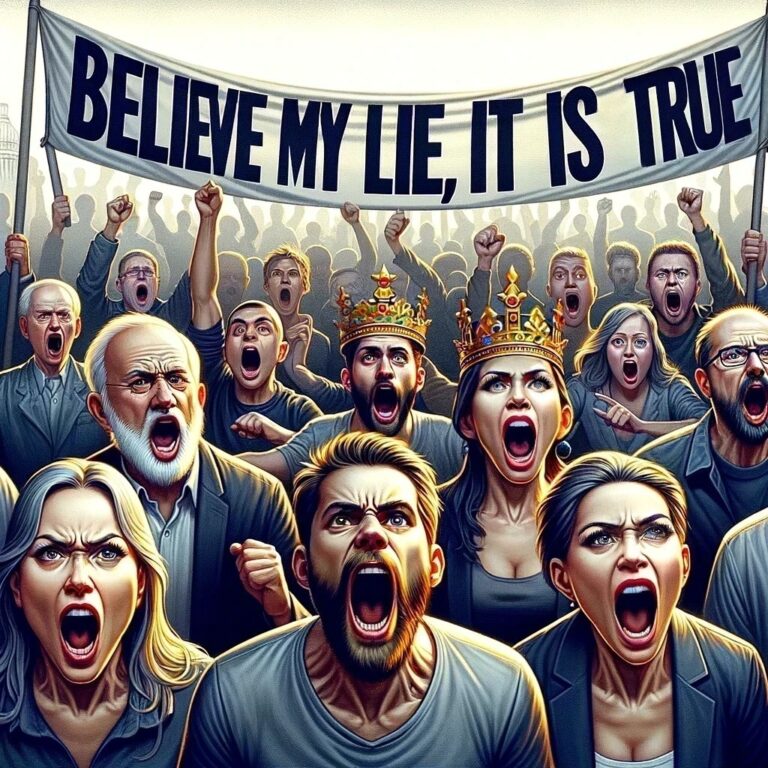

As The Economist According to the memo, misinformation from leaders has always existed. What has changed is the scale of private disinformation and the private amplification of government disinformation. The spectacular decline in the costs of producing and disseminating disinformation has multiplied it. The danger comes as much from the left as from the right, in particular from their populist wings. If you are “the people”, your lies become reality.

Thirty years ago, an observer of human affairs knew that everything he read or heard on television had been in private checked by some guards. A story and its source had been vouched for by at least one journalist and its editor, not to mention media owners who had a brand to protect. Likewise, ideas and authors of books had to pass through private gatekeepers in the publishing industry. Self-publishing was very expensive and identified the author as unknown and potentially unreliable (or uninterested in novels or poetry). Since Gutenberg, many documents of dubious value have been published (think Marxism), but their distribution entailed high costs and the reader actually had to purchase publications or go to a library to read them. Even after the invention of radio and television, where people like Father McLaughlin were numerous, some private monitoring services were provided by station owners or by those who financed maverick broadcasters. Without preventing the circulation and contestation of ideas, the cost barrier has eliminated much of the snake oil.

Nothing was perfect, of course, but what followed held new dangers. What the World Wide Web did from the mid-1990s and social media from the first decade of the 21st century was allow anyone to spread ideas and misinformation globally at a cost. very low (ultimately, only the speaking time of the speaker or repeater is sufficient). ). AI further reduces this cost: you don’t even need to know how to write (that is, put words one after the other in a coherent speech) to produce disinformation. From the reader’s or listener’s perspective, distinguishing serious heterodox ideas from pure misinformation has become more costly, although AI will also provide tools to uncover fakes.

What is the danger? Beyond a certain point, no free (or more or less free) society can be maintained. A self-regulated social order must collapse when a certain proportion of its members become hopelessly confused between what is true and what is false, or come to believe that truth does not exist. Even free agreement between individuals (commerce is a paradigmatic example) becomes too costly as the probability that someone is a liar or a fraud increases. We don’t know where the tipping point is. But we know that it was reached in countries like Russia (and the former Soviet Union) or China (despite a glimmer of hope after the fall of Maoism and its Red Guards). At this stage, only an authoritarian, or even totalitarian, government can coordinate individual actions, Military Man.

*****************************

By Pierre Lemieux and DALL-E