Steve Rosenberg,Editor Russia, in Ivanovo

BBC

BBCIf the billboards in Ivanovo are to be believed, Russia is truly on the move.

“Record harvest!”

“More than 2,000 km of roads repaired in the Ivanovo region!

“Change for the better!”

In this town, a four-hour drive from Moscow, a giant banner glorifying the Russian invasion of Ukraine covers the entire wall of an old cinema. With photos of soldiers and a slogan:

“To victory!”

These posters represent a country moving towards economic and military success.

But there is one place in Ivanovo that paints a very different picture of today’s Russia.

I’m standing outside. There is also a poster here. It is not a Russian soldier, but a British novelist. George Orwell’s face looks out at passers-by.

The sign above points to the George Orwell Library.

Inside, the small library offers a selection of books about dystopian worlds and the dangers of totalitarianism.

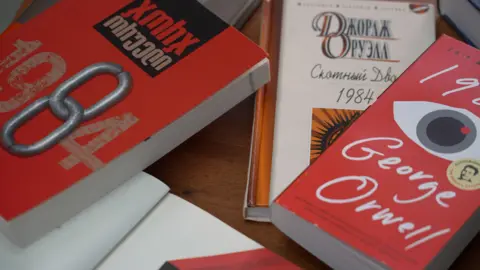

There are several copies of Orwell’s classic novel 1984; the story in which Big Brother is always watching and the state has established near-total control over body and mind.

“The current situation in Russia is similar to that of 1984,” librarian Alexandra Karaseva told me. “Total control of the government, the state and the security structures.”

In 1984, the Party manipulated people’s perception of reality, so that the citizens of Oceania believed that “war is peace” and “ignorance is strength”.

Russia today has a similar feeling about this. From morning to night, state media claim that Russia’s war in Ukraine is not an invasion, but a defensive operation; that Russian soldiers are not occupiers, but liberators; that the West is waging a war against Russia, when in reality it was the Kremlin that ordered the full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

“I have met people who are addicted to television and think that Russia is not at war with Ukraine and that the West has always sought to destroy Russia,” Alexandra explains.

“It’s like 1984. But it’s also like the novel Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury. In this story, the hero’s wife is surrounded by walls that are essentially television screens, talking heads telling her what to do and how to interpret the world.

A local businessman, Dmitry Silin, opened the library two years ago.

A vocal critic of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, he wanted to create a space where Russians could “think for themselves, instead of watching television.”

Dmitry was subsequently prosecuted for “discrediting the Russian armed forces.” He was accused of having scribbled “No to war!” » on a building. He denied the accusation. He has since fled Russia and is wanted by police.

Alexandra Karaseva shows me around the library. It’s a treasure trove of literary titans, from Franz Kafka to Fyodor Dostoyevsky. There is also non-fiction; the stories of the Russian Revolution, Stalinist repressions, the fall of communism, and modern Russia’s failed attempts to build democracy.

The books you can borrow here are not banned in Russia. But the subject is very sensitive. Any honest discussion about Russia’s past or present can lead to problems.

Alexandra believes in the power of the written word to bring about change. That’s why she’s determined to keep the library open.

“These books show our readers that the power of autocratic regimes is not eternal,” says Alexander. “That every system has its weak points and that anyone who understands the situation around it can preserve their freedom. Freedom of the brain can give freedom of life and country.

“Most of my generation had no experience of basic democracy,” recalls Alexandra, 68. “We helped destroy the Soviet Union, but we failed to build democracy. We didn’t have the experience to know when to stand firm and say, “You must not do this.” Perhaps if my generation had read Ninety-Eighty-Four, they would have acted differently.

Eighteen-year-old Dmitri Shestopalov read Ninety-Eighty-Four. Now he volunteers at the library.

“This place is sacrosanct,” Dmitry told me. “For young creatives, it’s a place where they can find like-minded citizens and get away from what’s happening in our country. It is a small island of freedom in an unfree environment.

As far as the islands are concerned, it is indeed little. Alexandra Karaseva is the first to admit that the library has few visitors.

On the other hand, I find a large crowd in the center of Ivanovo. It’s not Big Brother that people stopped to listen to. It’s a Big Band.

Under bright sunshine, an orchestra plays classic Soviet melodies and people start dancing to the music. As I talk to the crowd, I realize that some Russians are more than willing to believe what the billboards tell them, that Russia is booming.

“I am satisfied with the direction Russia is taking,” Vladimir, a retiree, told me. “We are becoming more independent. Less dependent on the West.

“We are making progress,” says a young woman named Natalya. “As Vladimir Putin said, a new stage has begun for Russia. »

But what about Russia’s war in Ukraine?

“I’m trying not to watch anything about it anymore,” Nina tells me. “It’s too upsetting.”

Back at the George Orwell Library, they are hosting an event. A local psychologist finishes a lecture on overcoming ‘learned helplessness’ and believes you have the power to change your life. There are ten people in the audience.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt the end of the conference, librarian Alexandra Karaseva announces the news.

“The building has been put up for sale. Our library has to move. We have to decide what to do. Where do we go from here?”

The library was offered smaller premises across the city.

Almost immediately, a woman offers her van to help him move. Another person in the audience announces that they will donate a video projector to help the library. Others suggest fundraising ideas.

This is civil society in action. Citizens come together in times of need.

Of course, the scale is tiny. And there is no guarantee of success. In a society where there is less and less room for “small islands of freedom”, the long-term future of the library is uncertain.

But they don’t give up. Not yet.