In a previous postI have argued that over 100% of inflation since late 2019 has been demand driven. There have been some negative supply shocks around 2021-22 that have led to significant inflation, but there have also been major positive supply shocks (notably immigration) that have tended to push inflation down. In net terms, cumulative inflation is entirely demand driven

I view nominal GDP growth as a useful indicator of the contribution of demand. Given that real GDP tends to grow by about 2% per year on average, a nominal GDP growth rate of 4% is a useful benchmark for appropriate monetary policy. Since late 2019, cumulative excess nominal GDP growth has been about 11% (or more than 4%), which can more than fully explain cumulative excess PCE inflation of about 9% (more than 2%).

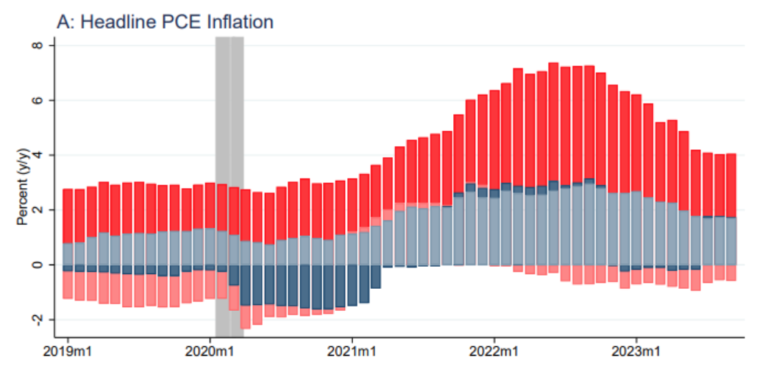

Most economists clearly don’t see it that way. Most of them seem to view the high inflation of 2020-24 as the result of a combination of supply and demand shocks. A recent San Francisco Fed working paper Adam Hale Shapiro provides a decomposition of inflation into supply and demand sides, which is broadly consistent with estimates I’ve seen from a number of economists:

Note that both negative supply shocks and positive demand shocks play a major role, with negative supply shocks being particularly important for headline inflation (which includes food and energy prices).

Shapiro uses an interesting technique to highlight the contributions of supply and demand shocks:

Since inflation is constructed as the weighted sum of category-level inflation rates, it is straightforward to split inflation by category or group of categories. I separate each month categories where prices moved because of an unexpected change in demand from those where prices moved because of an unexpected change in supply. The methodology is based on standard theory about the slopes of supply and demand curves. Changes in demand move prices and quantities in the same direction along the upward-sloping supply curve, while changes in supply move prices and quantities in opposite directions along the downward-sloping demand curve.

To say that I have mixed feelings about this is an understatement. I am very supportive of the technique of looking at joint movements in prices and output to identify supply and demand shocks, but I strongly object to drawing conclusions about aggregate price changes by aggregating sectoral price changes.

One of my first published articles (JPE, 1989, co-authored with Steve Silver) studied the cyclicality of real wages. We tried to estimate the extent to which the cyclicality of real wages depended on whether the economy was hit by supply or demand shocks. We identified these two types of shocks by looking at periods when prices and employment were moving in the same direction (demand shocks) and periods when prices and employment were moving in opposite directions (supply shocks). So I totally agree with this type of identification strategy. You can also compare the evolution of inflation to the evolution of real GDP growth rates. Indeed, my view that the period 2019-24 is entirely demand-side inflation is because growth was above trend – prices and output were moving in the same direction.

Shapiro studies data on prices and output for over 100 categories of goods and services. This is the part I disagree with (or perhaps don’t understand well enough). In any complex economy, some markets have positive correlations between prices and output, while others have negative correlations between prices and output. I worry that this technique leads to overstatements of the role of supply, because even in an economy where 100% of inflation is demand-driven, there are individual markets with negative correlations between prices and output (indicating supply shocks).

Consider a thought experiment with an economy characterized by a stable but high rate of inflation, driven by rapid monetary growth. Suppose also that the public has become accustomed to rapid inflation, so that wages and financial contracts take inflation into account. In other words, suppose that money is roughly neutral. You could imagine an economy in which the money supply doubles every 12 months and all wages and prices increase at a similar rate. Output would (assumedly) be at the natural rate. This would be an economy in which nearly 100% of inflation comes from demand (due to monetary policy). And yet, price-output correlations would vary considerably across sectors, because there would always be all sorts of changes in relative prices due to various local supply and demand shocks. In other words, the factors that affect relative prices in individual markets are radically different from the factors that affect the aggregate price level (monetary policy in this case, although velocity is another possibility).

Shapiro led me to a new study on Turkish inflation that leads me to believe that my thought experiment is more than just a hypothetical worry. Before looking at their study, consider how much inflation could result from supply-side factors. If monetary policy generates nominal GDP growth of 4%, you will end up with 2% inflation if output grows at its trend rate of 2%. But if adverse supply shocks reduce output growth to -1% and nominal GDP continues to grow at 4%, inflation will spike to 5%. So I have no problem with the claim that supply shocks could briefly push inflation 3 percentage points above trend. But what would it take for supply shocks to add 30% or 50% to a country’s inflation rate?

The Turkish study of Okan Akarsu and Emrehan Aktu ̆g produces this graph:

Note that Turkish inflation peaked at about 80% in 2022 and is generally much higher than that of the United States. Also note that the proportion attributed to supply and demand shocks is similar to the estimates presented in Shapiro’s chart for headline inflation. You might think this is not surprising—the Turkish authors used a similar model—citing Shapiro’s work. But I expect the contribution of supply shocks to be in an absolute sense Inflation rates should be relatively similar in both countries, say between 10 and 15 percent. If Turkey has a monetary policy that generates extremely high nominal GDP growth, I expect almost all of Turkey’s inflation to be demand-driven.

Here is the summary of the Turkish article:

We document the demand- and supply-driven components of inflation in Turkey following the decomposition method of Shapiro (2022). The results suggest that the recent rise in inflation, which started with the Covid-19 pandemic but deviates significantly from global inflation rates, was initially driven by supply-side factors but over time has transformed into an inflationary environment driven primarily by demand forces. Consistent with the theory, oil supply and exchange rate shocks increase the supply-driven contribution, while monetary policy tightening reduces the demand-driven contribution to inflation. This decomposition can potentially serve as a useful real-time monitoring tool for policymakers.

The term “currency shock” is perhaps a source of disagreement. In my thought experiment where the money supply doubled every year, I assumed that wages and prices also doubled. And a very important price is the price of foreign currencies, otherwise known as the “exchange rate.” So one year it might take 100 Turkish liras to buy one US dollar, then a year later 200 liras, then 400 liras, then 800 liras. I suppose this could be considered an “exchange shock,” but to me it is just one aspect of demand-side inflation, which pushes up all prices, including the price of foreign currencies.

We are so far apart that I wonder if the problem is not terminology. The terms “supply” and “demand” were developed to explain changes in relative prices in specific markets for goods and services, not changes in aggregate prices. There has always been a divide between those who prefer to view inflation as a depreciation of the purchasing power of money, caused by changes in the supply of and demand for money, and those who view it instead as the sum of individual price increases, caused by supply and demand factors in a wide range of markets. I am on the monetarist side of this divide.

For the concept I am interested in, it might be better to use entirely different terminology. For example, I could use the term “nominal inflation” for any change in inflation that is associated with changes in nominal GDP growth. And I could use the term “real inflation” for any change in inflation that is caused by changes in real output, holding nominal GDP constant. Of course, these terms would then be accounting terms only and would have no causal implications. I think that nominal GDP growth is ultimately determined by monetary policy (including monetary policy errors of omission), but this kind of causal claim requires evidence, it is not a mere tautology.

Anyway, I may be missing something obvious here, and I would be interested to know how others view claims such as the estimate that half of Turkey’s 80% inflation in 2022 is due to supply. Does this seem plausible to you? If so, what is your definition of “supply”?

I have never seen a clear definition of supply-side and demand-side inflation. In the absence of consensus, every empirical study on the issue becomes a de facto definition. There may be no real debate, just differing definitions.

PS. There is a method that shows supply inflation. even lower than my estimates. Some argue that any increase in real output tends to lower prices. Thus, if real GDP increases by 2% and nominal GDP by 4%, it can be argued that supply has lowered the price level by 2%, all else being equal, and demand has raised prices by 4%, resulting in net inflation of 2%.