In my last OLLI conference, “Economic growth: crucial but uncertain”, which I job and which I talked about on Substack, I did not discuss a question asked by one of the participants. I didn’t think about it because John, the AV guy, made some cuts and for some reason that question and my answer aren’t on the video.

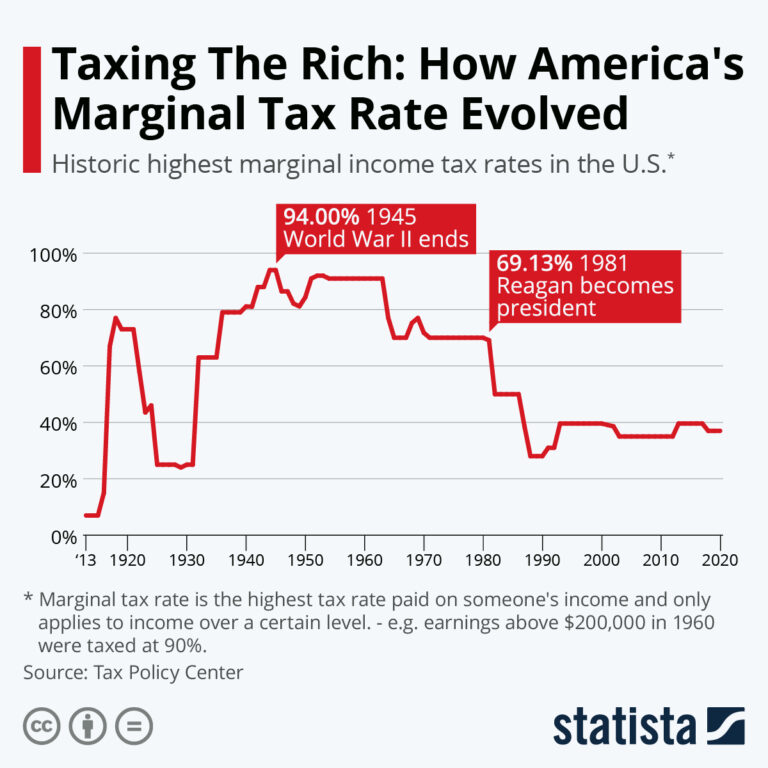

I gave the audience a quick overview of the highest marginal rates during the 20th century: 7% when the first income tax was implemented; 77% under Woodrow Wilson; up to 25% under Treasury Secretary Mellon (which worked its way through the Harding and then Coolidge administrations; up to 63% under Herbert Hoover then 79% in peacetime under FDR and up to 94% during the latter part of the war under FDR; then up to 91% during most of the 1950s and early 1960s; then up to 70% under LBJ (under the Kennedy tax cut); up to 50% at the start of the Reagan administration and 28% at the end of the Reagan administration to 31% under George HW Bush, etc.

Of course, I made a more summary statement than the one above, but the audience understood.

One of the audience members, a certain Ed, said: “Don’t the high marginal tax rates in the 1950s mean that high tax rates don’t matter much to economic growth since growth was quite good in the 1950s?

I responded that the top marginal tax rates applied to a very high level of income and that you had to adjust for inflation to see how irrelevant they were for more than 90% (and probably more than 95%) of employees. (I use “income” loosely; if I own stocks that earn me a nice dividend income, I count that income as earned.)

I could have given a better answer if I had the data at hand, and I’m about to do so. But I completely left out another answer: the economy was much less regulated in the 1950s than it is today. It was much easier to get a permit to build a house, a bridge, a pipeline, an office building. Plus, the accountability revolution that Walter Olson so eloquently wrote about hadn’t yet happened, so producers didn’t have to waste much effort idiot-proofing their products. Etc. All of these positives can easily outweigh the downsides of high marginal tax rates for a small percentage of the population. (A caveat: We haven’t had deregulation of airlines, trucking, or railroads, and that has hurt somewhat.)

Now let’s move on to the tax data. The Tax Foundation provides data on tax brackets and tax rates from 1862 to 2021. here.

Look at the marginal tax rates for 1954. For married couples filing jointly, if you had $400,000 or more in taxable income, your marginal tax rate was 91%; for singles, the amount was $200,000. This rate, for the same income brackets, was the same from 1954 to 1963.

But $400,000 in 1954 was $4.66 million. Furthermore, the real income distribution as a whole is now higher, probably at least twice as high. This would therefore amount to imposing a marginal tax of 91% on a married couple whose taxable income is $9.32 million.

Certainly, marginal tax rates were much higher than current rates, even for much lower incomes. Consider again 1954. For a married couple with taxable income of $24,000, the marginal tax rate was 43%. In today’s dollars, $24,000 would be $280,000. So my argument is not as strong as I initially thought. On the other hand, there were no Medicare taxes and Social Security tax rates were much lower. In 1954, the combined SS tax on employer and employee was 4%, compared to 12.4% today. Plus, it was zero after an income of $2,400, or $28,000 in today’s dollars.

Here’s my speculation, although I don’t have time to do the math and check a lot of data. Until 1963, for more than 80 percent of U.S. taxpayers in the top half of the income distribution, marginal tax rates, including Social Security and Medicare, were lower than they would be. Today, more than 80% of taxpayers are in the upper half of the income distribution. .