Kevin Corcoran recently published an article on the distinction between being wrong in theory and being wrong in fact. Here I am interested in another situation, one where theory matches reality quite closely, but people are reluctant to accept the implications of this fact. For example, basic economic theory suggests that higher tax rates should reduce hours worked. Europe has higher tax rates than America and significantly fewer hours worked each year. But many people seem reluctant to accept the direct implications of these facts.

The Economist has a very good article on this subject:

Edward Prescott, an American economist, came to a provocative conclusion, saying that the key was taxation. Until the early 1970s, tax levels were similar in America and Europe, as were hours worked. By the early 1990s, European taxes had become heavier and, according to Prescott, employees were less motivated. A significant gap persists today: American tax revenues represent 28% of GDP, compared to around 40% in Europe.

Note that Prescott draws on two types of evidence, both cross-sectional and chronological. This makes his claim much more convincing than a simple comparison of two places at one time. And yet, many are reluctant to accept the obvious implications of these facts.

The article presents an empirical study that suggests that the work disincentive effects of high taxes may be rather modest:

A recent study by Jósef Sigurdsson of Stockholm University examined how Icelandic workers responded to a one-year income tax holiday in 1987, when the country overhauled its tax system. Although more flexible people – particularly younger people in part-time jobs – did indeed work more hours, the overall increase in work was modest compared to that implied by Prescott’s model.

Again, this result is not at all surprising. Because of the “collective action problem” aspect of the labor structure, one would expect the short-run elasticity of labor supply to be much lower than its long-run elasticity. Decisions about work schedules are usually made at the corporate level, and even to some extent at the societal level (such as things like school schedules, which must be coordinated with work schedules.) It is appropriate to note that the elasticity was higher for young part-time workers. , which face fewer coordination problems.

How can we explain the reluctance to accept the obvious implications of a theory? A few more examples will help illuminate the sources of bias:

1. Theory suggests that higher levels of CO2 should increase global temperatures due to the “greenhouse effect.”

2. Theory suggests that injecting a lot of money into the economy should cause price inflation (i.e., reduce the purchasing power of a single dollar bill).

It would be quite surprising if more CO2 did not cause global warming, or if large injections of money did not cause inflation. And yet, I often encounter people who disagree with these statements. They might claim that global warming is an unproven theory or that inflation is caused by corporate greed. Why reject evidence that fits standard theory almost perfectly? What is happening here?

I notice that people who believe in the inflation theory of corporate greed also tend to have left-wing political views, while those who are skeptical of global warming tend to have right-wing political views. This perhaps explains why so many people are skeptical of the claim that high taxes discourage the work effect.

Suppose you favor a large welfare state, for various reasons. In this case, you might be reluctant to accept empirical data suggesting the negative effects of high taxes. From a purely logical point of view, this doesn’t make much sense. It is certainly possible that a welfare state will be beneficial even if it leads to a reduction in GDP per capita. Perhaps the extra leisure is worth it for the national income.

Unfortunately, when people have strong political opinions, they become more like lawyers than scientists. They look for any evidence that appears to strengthen the arguments for their policy preferences and discard evidence that weakens the arguments for their policy preferences.

Political bias is not the only factor that causes people to reject the implications of economic theory. It is also true that many economic theories are counterintuitive. For example, most elasticities tend to be higher than one would expect based on introspection, that is, “common sense.” So even people suffering from so-called “addictions”, such as smoking or illegal drug use, often react in surprising ways to price signals.

Many people probably have a hard time imagining how higher taxes would cause them to work fewer hours. They might think, “With higher taxes, I’ll have to work more hours to pay my bills.” » Their mistake is not recognizing that tax revenues do not disappear, they are recycled in the form of profits for those who consume more leisure. This is what economists mean by “income-adjusted labor supply elasticity.”

To summarize:

1. When the theory suggests that X is true.

2. And when empirical evidence tends to confirm the theory.

Be very careful before rejecting the claim that X is true.

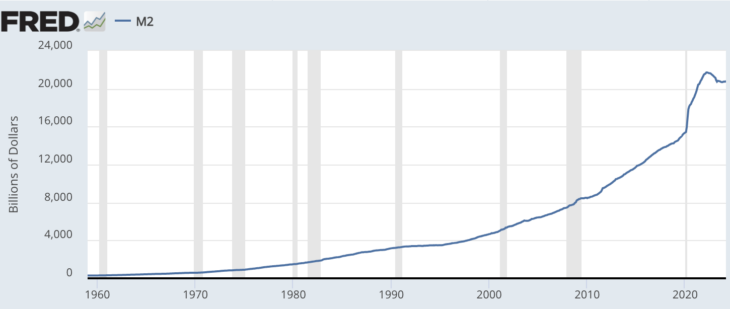

PS. Suppose you go back in time and show David Hume the following graph for the M2 money supply:

If Hume had been asked what he thought had happened to inflation in the early 2020s, what would he have said? Suppose then that you told Hume that many people now blame “corporate greed” for the high inflation of the early 2020s. What impact would this information have on Hume’s view of progress in the field of economics in the 270 years following the development of the quantity theory of money?