Today’s jobs report contains two pieces of information that suggest policy might be a little too expansionary. First, payroll employment increased by 272,000 more than expected. (The household survey was weak, but this data is considered less reliable.) Second, nominal wages increased by 0.4% (an annual rate of almost 5%). Considering the Fed’s dual mandate, both data point to slightly tilting the scales toward the idea that policy is too expansionary. This does not mean that we can be certain that policy is too expansionary, just that this statement is now a little more likely to be true.

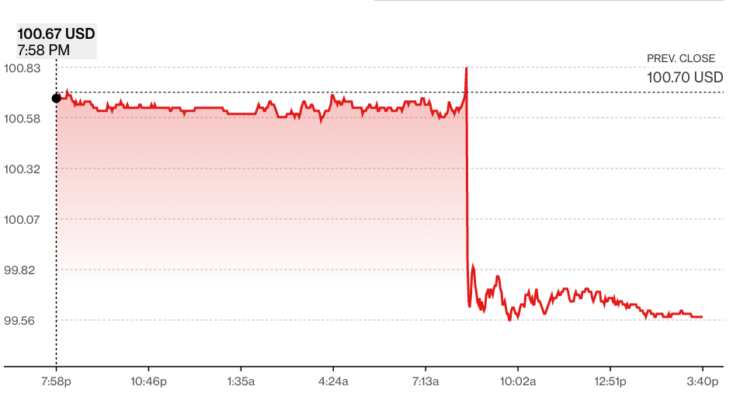

The 10-year Treasury bond market responded with a sell-off, meaning long-term interest rates rose:

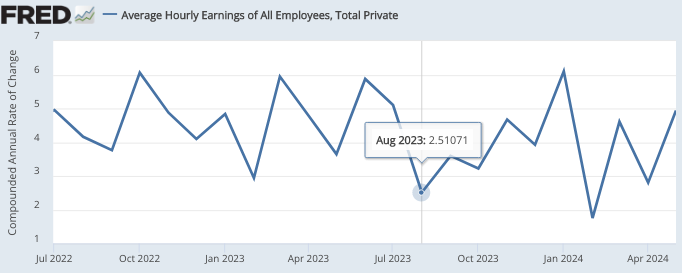

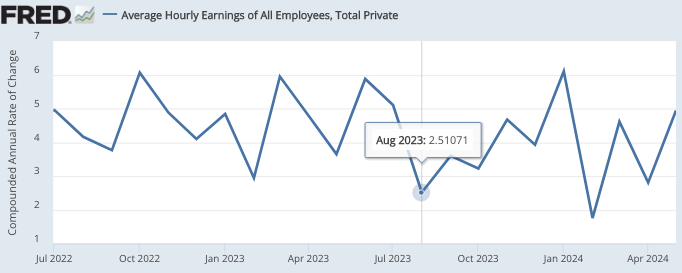

Markets are currently pricing in a Fed rate cut later this year. This may happen because inflation is falling or because the real economy is at risk of falling into recession. Today’s news makes both of these outcomes a little less likely. Wage inflation has averaged 4.1% over the past 12 months, a rate that is not consistent with the Fed’s “price stability” goals, even if one defines stability prices like 2% inflation. Over time, wage inflation tends to exceed price inflation by about 1 to 1.5 percent. Unfortunately, progress in reducing wage inflation appears to have stalled over the past ten months. The next two or three readings will be very important.

I don’t have a strong opinion on where the Fed should set its interest rate target at this time. I have strong opinions about past monetary policy, which has been far too expansionary over the past three years. The longer these policy overruns last, the stronger the case for moving to a level-targeting policy regime, in which the Fed would commit to making up for previous policy errors. I thought they intended to do this in 2020, but it turns out that “average inflation targeting” was not an accurate description of their new policy regime.

This post is entitled “double trouble”, even if the salaried employment figure can be considered good news. These figures are problematic for a Fed which seems to hope to soon be able to lower its target interest rate. In my opinion, it is a mistake for the central bank to advocate lower interest rates, just as the Fed was a mistake to favor higher interest rates in 2015. It should not favor neither lower interest rates nor higher interest rates; they should promote (nominal) macroeconomic stability. Let the market decide what types of interest rates are consistent with macroeconomic stability.

PS. This comment in flight caught my attention:

Jason Furman, a former Harvard University administration official, said rising unemployment may be the most important part of the data released Friday.

“If we wake up next month and the unemployment rate hits 4.1 percent, I think that will get (the Fed’s) attention,” Furman said. “If you have an unemployment rate above 4, that would put rates lowering sooner into play.”

In the 1970s, the Fed considered a rise in the unemployment rate to be a sign of a liquidity shortage. This was not the case. The Fed should never target the unemployment rate, because no one knows exactly what the natural unemployment rate is at any given time. The Fed should target variable nominal GDP, preferably. It is often true that rising unemployment is a sign that easier financing is needed, but not if the NGDP is growing at 5%.