Almost everyone seems to think it, including many economists: when a price rises, it fuels inflation. The venerable magazine The Economist Don’t think twice about it. Speaking of Argentina, he writes (“Javier Milei’s next move could make or break his presidency», June 19, 2024):

Monthly inflation could rise in June as energy prices rise.

THE Wall Street Journal headline a headline saying “Rent increases loom, which threatens the fight against inflation», June 18, 2024. Examples are everywhere.

But if each price increase fuels inflation (a general rise in the price level), each price drop must threaten deflation (a general fall in the price level, observed in recessions). All things being equal, every price drop in the market is a threat, as is any price increase. Every price change is a bad omen. Is this strange theory valid? The error lies in not distinguishing between changes in relative prices and changes in the general price level, that is to say of all prices, which is inflation (or deflation).

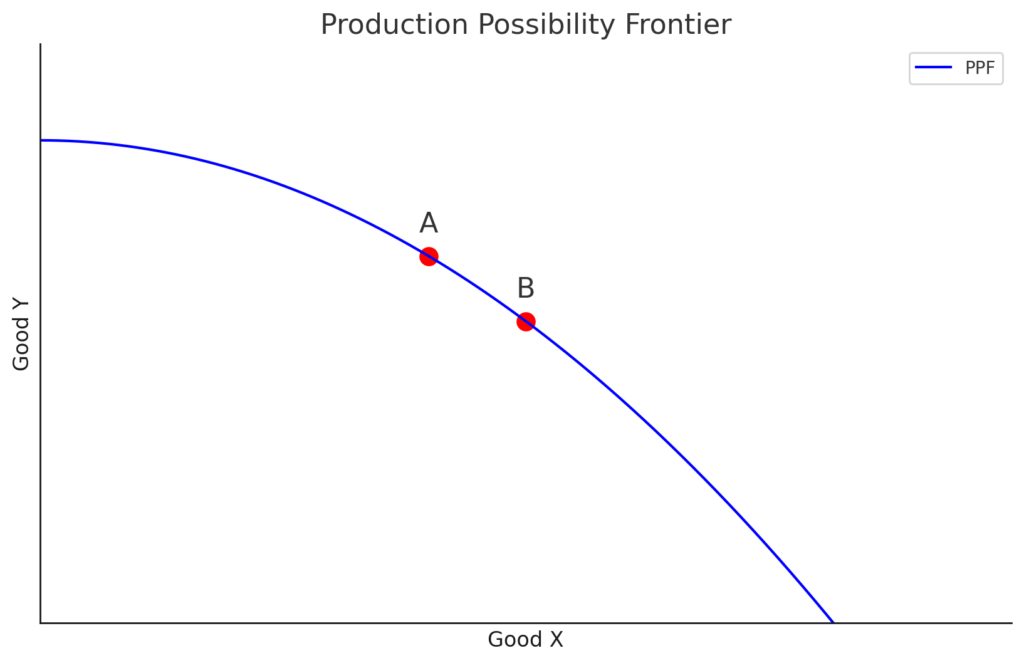

Imagine there is no inflation or deflation and the demand for beef increases, all else being equal. As a result, the price of beef increases relative to (say) pork. This means that the economy has crossed its production possibilities frontier (PPF) towards more beef and less pork, implying that beef now costs more than pork. (The chart below shows a standard PPF for an economy with two goods. If good Y is beef and good X is pork, the economy has moved from point B to point A.) Any price index ( for example, the consumer price index) have changed between the initial situation B and the new A on the PPF. Whether the index shows an increase or decrease will depend on the precise quantities of beef and pork, because these quantities constitute the weights with which the price index is calculated. It would be a coincidence if this did not change. Thus, we cannot use a change in a relative price to conclude that there is inflation or deflation.

Inflation – a general increase in the price level – is a different phenomenon, caused by the quantity of money in the economy.

Inflation – a general increase in the price level – is a different phenomenon, caused by the quantity of money in the economy.

If there is inflation, a price index captures both changes in relative prices and changes in the general price level. We cannot attribute part of inflation to the change in a specific price, because the latter change is partly due to inflation (the way all prices have increased) – and partly to the change in this price compared (relative) at other prices. Rents or energy prices cannot fuel inflation (or deflation) because they are part of the cause. Causality works the other way.

I’ve written a few EconLog articles on this topic, but my recent article, “Rising Product Price Does Not Cause Inflation,” in Ryan Bourne, Editor-in-Chief, The war on prices (Cato Institute, pp. 19-27) provides a more detailed explanation. My message “Guns and Butter» contains another illustration of the PPF concept.

*****************************

Does a fall in prices fuel deflation? By DALL-E and your humble blogger