Sarah Rainford,Eastern Europe Correspondent

BBC

BBCAt 12, Lera learned to walk again. Shy steps at first, but more confident with each one.

Last summer, a Russian missile attack broke his leg and severely burned the other.

Nearly 2,000 children have been injured or killed in Ukraine since Vladimir Putin launched his full-scale invasion. But war doesn’t always leave visible scars like those running down Lera’s leg.

“Almost all children have problems caused by war,” explains psychologist Kateryna Bazyl. “We are seeing a catastrophic number of children coming to us with various unpleasant symptoms. »

Across Ukraine, young people are experiencing loss, fear and anxiety. A growing number of people are having trouble sleeping, having panic attacks or flashbacks.

There has also been an increase in cases of childhood depression among a generation that grew up under fire.

Lera Vasilenko, 12, in Chernihiv, northern Ukraine

Lera saw the missile that injured her seconds before it hit.

It was a hot summer vacation and the center of Chernihiv was busy. She and her friend Kseniya were trying to sell their homemade jewelry to the passing crowd.

“I saw something flying up and down. I thought it was some kind of plane that was going to come up, but it was a missile,” Lera said, the words crashing out at high speed as if she didn’t want to dwell on their meaning.

After the explosion, she ran back and forth in panic on her mangled leg before realizing she had been injured.

“People say I was in shock. It was only when Kseniya said: “Look at your leg!” that I felt the pain. It was horrible.”

At the start of the all-out war in 2022, the bombing of Chernihiv in northern Ukraine was constant. But within weeks, the Russian forces were pushed back. Life is gradually returning to the city.

Then, on August 19, 2023, the local theater hosted an exhibition of drone manufacturers and Russia attacked. Shards of metal flew through the streets all around.

Nine months later, Lera lifts her pant leg to reveal multiple deep scars and a skin graft. There is a large bump where metal implants were inserted.

The wounds are healing well and she moves nimbly with her crutches. But she still has difficulty hearing the sound of air raid sirens.

“If they say a missile is heading towards Chernihiv, I go crazy,” she admits. “It’s really bad.”

She insists that she’s coping and hasn’t changed, but her sister isn’t so sure. “You’re more explosive,” Irina told him. Lera nods sheepishly. “I wasn’t that aggressive before.”

It’s one of many reactions child psychologists observe to the stress of this war.

“Children don’t understand what happened to them, or sometimes the emotions they feel,” says Iryna Lisovetska, of the charity Voices of Children, which helps hundreds of young Ukrainians across the country.

“They may display aggression as a form of self-protection.”

For Lera, the war was doubly cruel.

A few months before she was injured, her brother was killed fighting on the front lines. The two were close and Lera is still having a hard time accepting Sasha’s departure.

“I imagine he’ll call any time.” I used to see his face in people passing by on the street. I still can’t believe it,” she says softly, wrapped in a Ukrainian flag that she plans to take to Sasha’s grave. A replacement for the one frayed by the wind.

Without warning, Irina bugs her phone and Sasha’s deep voice fills the room. “I really love you,” the soldier assures his sisters in a final audio message sent from the front.

This is the first time Lera has heard his voice since his death. His chin trembles with emotion.

Daniel Bazyl, 12, in Ivano-Frankivsk, western Ukraine

Daniel’s greatest fear is suffering a loss, like Lera.

His father is a soldier serving near their hometown of Kharkiv, where fighting has intensified.

Russian troops recently crossed the border in a surprise offensive, gaining ground, as missile attacks on the city have increased. Among those killed last week was a 12-year-old girl who was shopping with her parents.

“Dad tells me everything is fine, but I know the situation there is not the best,” says Daniel. “Of course I worry about him.”

The 12-year-old now lives in western Ukraine with his mother, far from Kharkiv. Russian missiles reach Ivano-Frankivsk, but you get a lot more warning. The streets are crowded and relaxed. There are even traffic jams.

But even here, Daniel cannot escape the conflict. He recorded a prayer above his bed that he recites every evening for his father’s safety, although he had never been religious before.

He and his mother, Kateryna, were refugees for a time. They returned to Ukraine because she is a child psychologist and saw the urgent need for her skills.

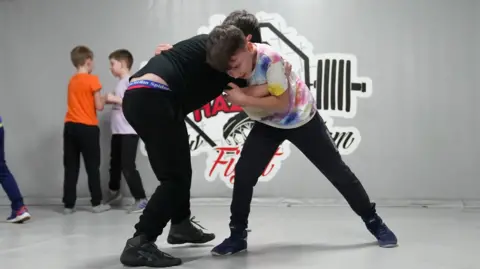

She does her best to distract her own son with endless activities: there’s a skate park and guitar lessons. He’s taken to the streets to raise money for the Ukrainian army, and there’s a fight club to help him stand up to school bullies.

“I tried to find things he liked before, continue to do them here, and it works,” says Kateryna.

But the boy from the northeast still has difficulty integrating.

“It really bothers me when there’s an air raid at school and everyone is happy to miss class,” Daniel says. “A siren here simply means going to the bunker. But this actually means that fighting is taking place elsewhere in Ukraine.”

Daniel counts the hours between online calls with his father. Her father sends her packages full of artistic materials so that he can teach her to draw, remotely.

“I want to believe that the war will end soon,” Daniel shares his greatest desire. This way he could return home to Kharkiv, he said.

“And that would be really cool.”

Angelina Prudkaya, 8, in Kharkiv, northeastern Ukraine

Eight-year-old Angelina is still in town, living in the middle of a bomb site.

She comes from the suburb of Saltivka, where Daniel also lives. When Russian troops first advanced into the region two years ago, they were in the crosshairs and Angelina was sheltering with her family in their basement.

“It was very scary. I was just thinking: when will this all end? There were rockets and a plane flew over us,” the little girl recalls, pulling at the sleeves of her sweater.

In early March 2022, the giant building next door was destroyed by a missile.

Anya, Angelina’s mother, told her to cover her ears and lie down quietly.

“I thought we would be buried under the ruins. That our building had been hit and was going to collapse,” she said, her eyes widening at the memory.

After that, they fled.

But when Ukrainian forces liberated the northern region last year, the family returned to Saltivka. They are the only ones living in their apartment building, surrounded by smoke-blackened buildings and broken glass. Despite the shrapnel in the kitchen wall, it’s home.

Today, Kharkiv is a nervous place again. The bomb attack on a DIY store last weekend happened near Angelina’s apartment.

Vladimir Putin says he has no intention of taking the city, but Ukrainians have learned never to trust him.

“When they start bombing, I tell mom I’m going into the hallway and she sits there next to me,” Angelina says with the calmness of too much experience.

Moving towards the hallway creates an additional wall between your body and any explosions. This is minimal protection.

Angelina should have already started at her local school, but there’s a hole dug in the side. She barely remembers kindergarten because before the invasion, there was Covid.

Anya tries to combat loneliness by taking her daughter to activity sessions, including pet therapy. It is run by the children’s charity Unicef, underground in the metro for added safety.

Throwing balls for a bright dog named Petra, Angelina comes alive in peals of laughter.

But when evening falls on his house, the lights no longer come on. Russia targets electricity supply.

So Angelina lights a candle, carefully, her small figure casting a giant shadow on the wall of their apartment. “It happens all the time,” she says, shrugging, of power outages.

Like Lera and Daniel, Angelina adapts as best she can to this war.

But across the country, demand for support is growing.

“We tell children that they can feel everything they do,” says Kateryna Bazyl. “We’re saying we can help them understand how to control these emotions, not destroy everything around them. Or themselves.

When I wonder if there is enough help for everyone, she pauses.

“To be honest, we have a very long queue.”

Produced by Anastasia Levchenko and Hanna Tsyba

Photos by Joyce Liu