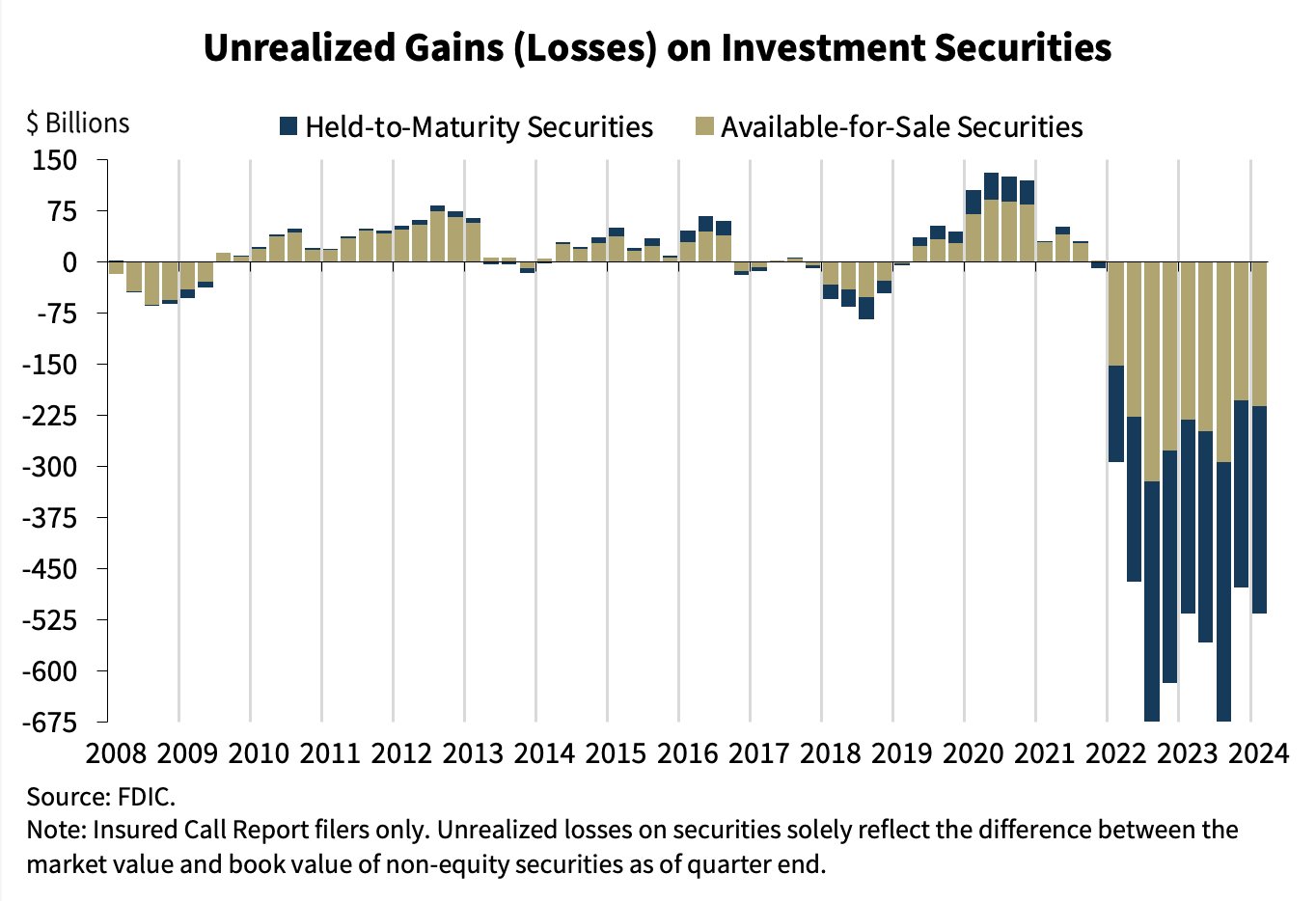

When interest rates rise, the price of long-term assets falls. As a result, when the Fed began raising interest rates in 2022, the value of bonds and mortgages fell, causing large accounting losses for banks heavily invested in these assets. Silicon Valley Bank went bankrupt, for example, because depositors fled after realizing it held many Treasury bonds.

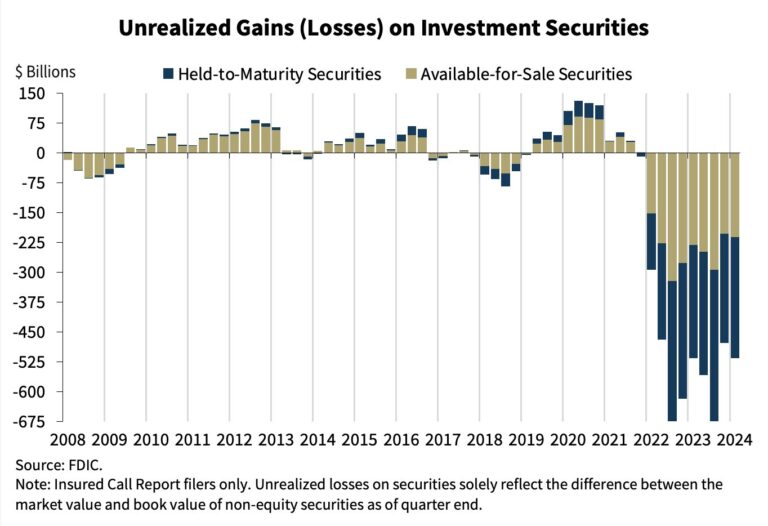

Interest rates remain high and many banks are recording large unrealized losses on their accounts. According to latest FDIC data (see below) Unrealized losses currently total $516.5 billion, far exceeding levels seen during the 2008-2009 financial crisis. Price risk is not the same as default risk and if banks can hold their assets to maturity then they will be solvent. The real danger, as with SVB, is that unrealized losses are combined with a run on deposits. So far this doesn’t seem to be happening, but it’s still entirely possible.

In other news, Hypertext has a problem dedicated to Anat Admati and Martin Hellwig The banker’s new clothes. Admati and Hellwig write:

In the United States, the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 promised an end to bailouts for banks and “too big to fail” institutions. The European Union’s 2014 legislation on banks at risk of failing would provide “a framework” to “deal with banks that are experiencing financial difficulties without using taxpayers’ money or endangering financial stability.” In November 2014, Mark Carney, then governor of the Bank of England and chairman of the Financial Stability Board (FSB), a global financial regulator, triumphantly announced that agreement on new rules for the thirty plus large and most complex financial institutions, “globally systemic,” would prevent bailouts in the future. Many political and media actors believed these claims.