The Economist has an article discussing the issue of forward guidance in monetary policy. Here is an exerpt :

To credibly guide expectations, managers must ultimately follow through on the changes they indicate. The dilemma is what to do when conditions change, as they have since Powell’s pivot, with inflationary pressures stronger than expected, making rate cuts less appropriate. Staying the course may no longer be appropriate; Changing it risks harming central bankers’ ability to stifle investors in the future. . . .

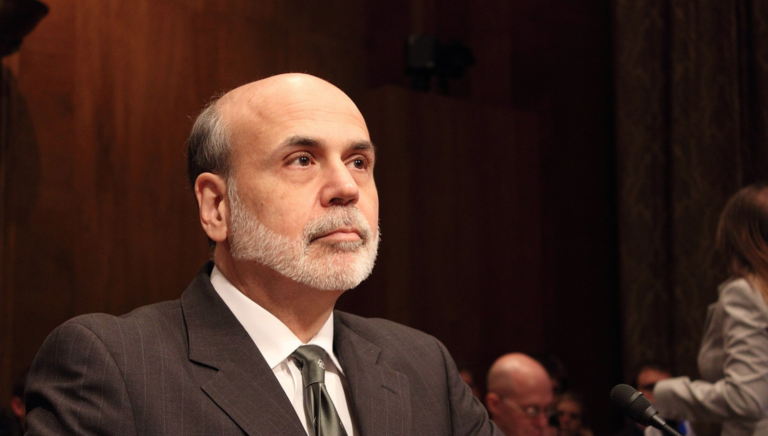

Former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke once warned that such considerations could quickly degenerate into a “hall of mirrors.” If policymakers imitate market expectations, which change accordingly, endless distortions are possible. Fittingly, Mr Bernanke’s most recent work, examining the Bank of England’s approach to forecasting, offers a way out, suggests Michael Woodford of Columbia University. A crucial recommendation was that the bank should start publishing its policy rate forecasts under a range of different economic scenarios, rather than just its central forecasts. This would help investors understand how policymakers would react to different conditions, allowing them to change course in response to new data without losing face.

In my view, conditioning interest rate forecasts on macroeconomic conditions is an improvement over unconditional forward guidance. Unfortunately, it is difficult to predict the impact that changing macroeconomic conditions might have on the future movement of the natural interest rate.

An alternative would be to offer more specific guidance regarding the Fed’s policy objectives. For example, one might imagine a nominal GDP target that calls for 4% annual growth, with catch-up policies to correct any short-term deviation from this trend line. This type of policy regime is called “NGDP level targeting” because it targets the NGDP level and not the growth rate.

Even more precise indications could be provided by specifying the exact nature of the makeup policy. For example, the Fed could indicate that the catch-up would occur at the rate of 1%/year, until returning to the trend line. So, if an error pushed the NGDP 1% above the target path, the Fed would target 3% growth over the next 12 months. If an error pushed the NGDP 2% above the target, the Fed would target NGDP growth of 3% over the next two years. If the NGDP fell 1.5% below the target, the Fed would target NGDP growth of 5% over the next 18 months.

One advantage of this type of policy regime is that it would make it easier to interpret information in interest rate futures markets. Today, policymakers are unsure whether an abnormal movement in federal funds futures reflects expectations about what kind of future interest rates would be needed to achieve 4% NGDP growth, or a lack of confidence that the Fed is actually trying to achieve 4% NGDP. growth. To be more concrete, if federal funds futures show that rates will fall to 3.5% over the next year, is that because markets are expecting a weaker economy, or is it Is it because markets expect an easy money policy that will trigger a stronger economy?

I advocated a “guardrail” approach, in which the Fed would take unlimited short positions in 5% NGDP growth futures and unlimited long positions in 3% NGDP growth futures. But even if this market-driven policy regime were politically unfeasible, a clearer statement of the Fed’s desired trajectory for NGDP growth would lead to an environment in which existing financial markets could provide a rich source of information to policymakers politicians who are wondering where to stand. their interest rate target.

I believe that setting a clear target for the NGDP level would significantly reduce the volatility of NGDP growth over time. Indeed, an NGDP level targeting regime with a clearly specified catch-up rule would likely have allowed us to avoid a serious recession in 2008-09, and a serious inflation overshoot in 2021-22.