Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution by Jamel Saadaoui (University of Strasbourg).

Commerce is a remedy for the most destructive prejudices… wherever we find agreeable manners, there commerce flourishes; and that wherever there is commerce, there are pleasant manners.

When two nations come into contact, they either fight or trade. If they fight, both lose; if they trade, both win.

Peace is the natural effect of commerce. Two nations that trade with each other become reciprocally dependent… their union is based on their mutual needs.

Montesquieu, The Spirit of Laws, 1748

In these few quotes, we can easily understand that the French philosopher Montesquieu (Charles Louis de Secondat, his real name, born in 1689 and died in 1755) had a positive vision of the effect of trade and exchange on political relations between two nations. Perhaps that was true in his time. Related to this question, Menzie Chinn recently wrote here on German trade relations before the First World War. Perhaps increased trade is not always a good indicator of peaceful relations. Montesquieu may be wrong.

An interesting question would be to test the case of China, whose emergence was not fully understood in the early 1990s (see here), expect business circles who were well aware of the enormous consequences of China’s takeoff. After China’s entry into the WTO on December 2001, China’s place in world trade has become increasingly important. This trend continued until the global financial crisis (GFC). Has this expansion of trade for China resulted in calmer relations with its trading partners over the past 60 years?

Antonio Afonso, Valerie Mignonand I study this question in a recent draft. In order to answer this question with empirical evidence and not rely solely on hunches, we need three ingredients, namely (1) variables that measure trade ties, (2) variables that measure tensions bilateral policies and (3) statistical tests that allow for time-varying causality. For trade links, we use the current account balance (to include the income balance) and the bilateral exchange rate with the US dollar (the dollar remains dominant in trade; see here). For bilateral political tensions, we use the Political Relations Index (PRI) constructed and maintained by Xuetong Yan and his team at Tsinghua University (see here). For time-varying non-causality tests, we rely on the test developed by Shi et al. (2020). We will focus on China’s important trading partners, namely the United States, the United Kingdom and Germany. We also look at three important late partners, India, Japan and South Korea.

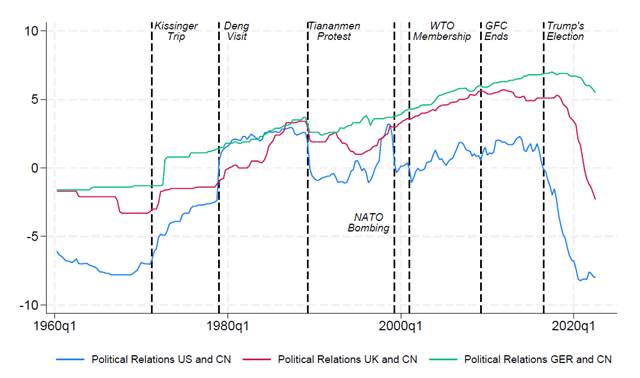

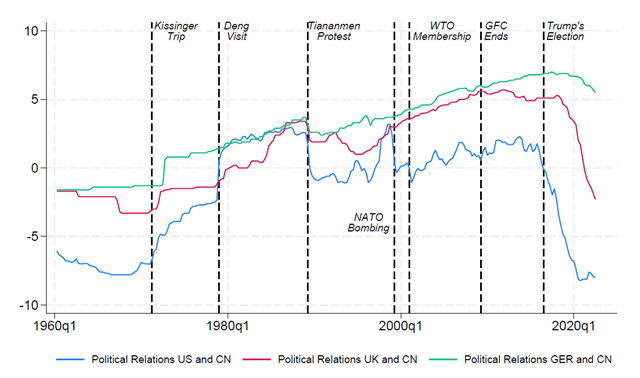

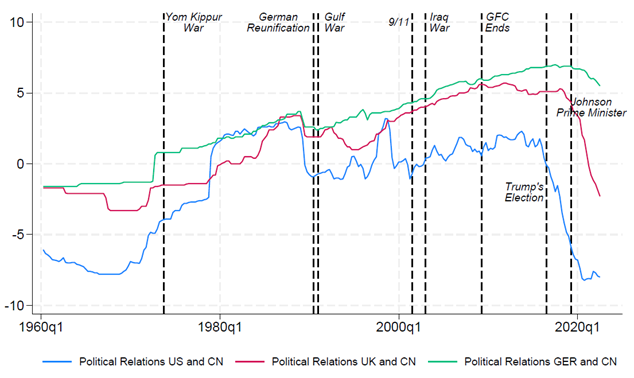

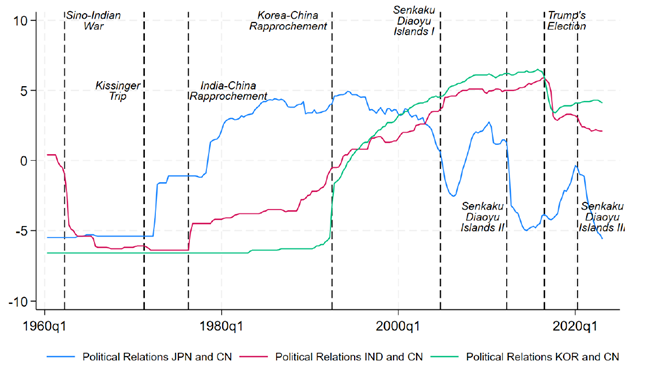

At this stage, we can question the quality of the PRI for measuring bilateral political tensions. In the following Figures 1 to 3, you will see that the fluctuations around the main events recur regularly.

Figure 1: Bilateral Political Relations Indices (PRI): Highlighting events between the United States and China

Figure 2: Bilateral Political Relations Indices (PRI): highlighting Europe-China events

Figure 3: Bilateral Political Relations Indices (PRI): Highlighting events between Asia and China

If you are sufficiently confident that these indices are reliable, we can now turn to testing for time-varying non-causality between business ties and political tensions to answer our question. In this article, we use another political measure, namely the ideal distance from China in the UN General Assembly votes (see here), as a robustness check. For bilateral exchange rates, we also add the VAR plus the lag, the GPR Index de Caladara and Iacoviello, and the VIX, because these two variables can influence the bilateral exchange rate.

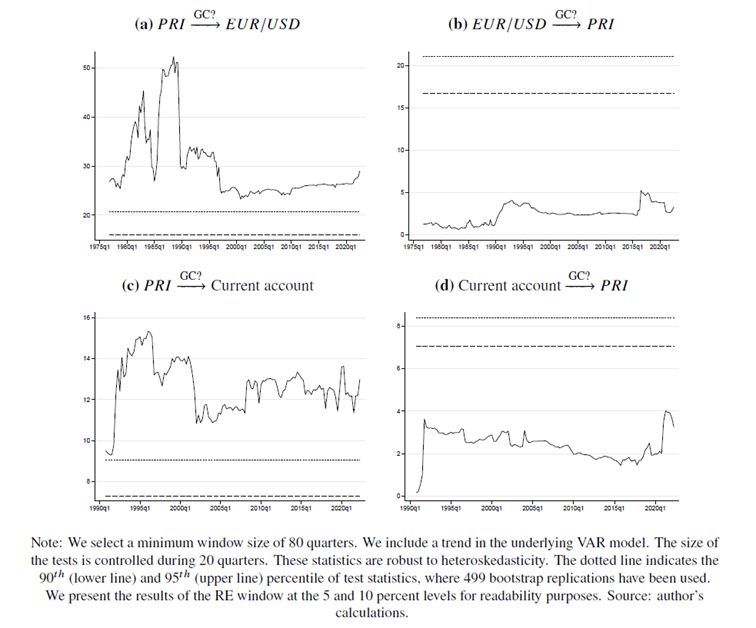

The case of Germany is particularly interesting. As Figure 4 shows, one-way causality runs from the PRI to the exchange rate and the current account for most of the period considered. At the global level, the continued improvement in political relations between China and Germany is accompanied by a depreciation of the CNY and growing current account surpluses, except at the end of the period when the tense relations which begin to emerge go hand in hand with the appreciation of the dollar. Chinese currency. After China’s entry into the WTO, relations between China and Germany have found themselves at the heart of global value chains. This special bond was strengthened during the enlargement to Eastern Europe in 2004, when Germany began to become the industrial core of this new EU with a center of gravity shifted to the East. Germany and China have become two major players in terms of trade flows (Miranda-Agrippino et al., 2020).

Overall, our results show that Montesquieu’s vision of “sweet commerce” does not always hold for the United States and the United Kingdom, and never for Germany. According to him, causality should flow from trade to political relations since commercial partnerships should produce more peaceful relations between individuals and nations. We find that the “soft trade” and “trade follows the flag” views are supported by empirical evidence at different times for the United States and the United Kingdom, illustrating the relevance of varying specification in the time. The most striking result is that “trade always follows the flag” for Germany and China: we reject the null hypothesis of non-causality running from political relations to macroeconomic variables, while the null hypothesis of non- causality of political relationships to macroeconomic variables is not true. rejected. This shows that good political relations were a prerequisite for the expansion of trade between China and Germany.

Figure 4: Time-varying causality for China and Germany

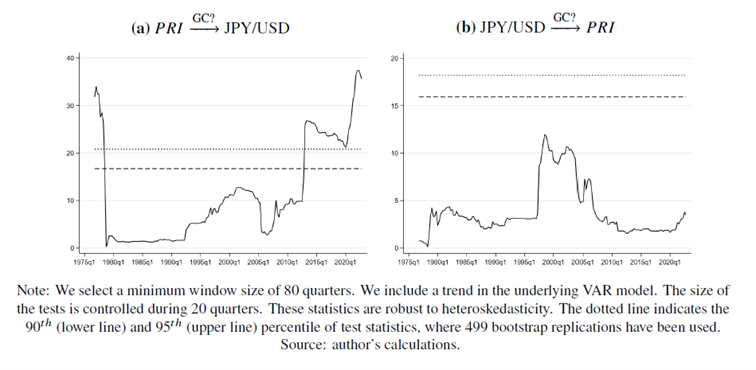

In the case of Asian partners, although there is no causality between the PRI and the exchange rate most of the time, it is significant in specific periods where particular events have occurred. Sino-Japanese relations generally followed an increasing trend until the early 2000s (Figure 5) and warmed considerably after Shinzo Abe – then Yasuo Fukuda – became Prime Minister of Japan in September 2006. A strong dispute between the two countries concerned the territoriality of the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands, which increased tensions. This deterioration in Sino-Japanese relations affected the yen exchange rate, as illustrated by the significant causality observed in Figure 5. Regarding Sino-Indian and Sino-Korean relations, they improved throughout period, explaining why causality from the PRI to exchange rates is mostly insignificant. The significant causality observed in the mid-1990s for the Indian case is explained by border problems and Indian nuclear tests, while it is notably the result of tensions linked to the breakdown of diplomatic relations between Taipei and Seoul. in 1983. Concerning reverse causality, for the exchange rate relative to the PRI, it is particularly significant in the 1990s for India, corresponding to a period of sharp depreciation of the rupee originating from current account deficits and d a loss of investor confidence.

Figure 5: Time-varying causality for China and Japan

This article written by Jamel Saadaoui.