In the period following the 2020 Covid pandemic, many countries experienced relatively high inflation. This reflects two factors:

1. All countries have been affected by shocks such as Covid-related supply chain disruptions and the war in Ukraine.

2. Most countries adopted very extensive stimulus programs, which had similar effects in each case.

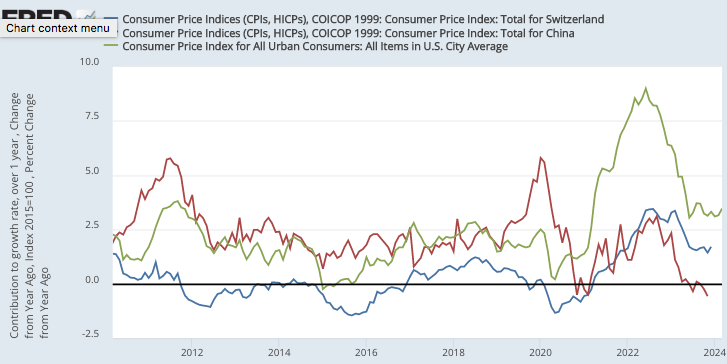

It was appropriate to allow some increase in inflation in response to negative supply shocks. This is the whole idea behind “flexible” average inflation targeting. But the real inflation rate also reflected excessive growth in aggregate demand and was therefore inappropriately high in many countries, including the United States. I worry when people seem to suggest that the Fed couldn’t have done much about the surge in inflation, because it also happened in many other countries. In fact, not all countries have experienced extremely high inflation. Note that China (red line) and Switzerland (blue line) have seen some increase in inflation, but much less than in the United States (green line):

In a podcast with David Beckworth, former Fed Vice Chairman Richard Clarida suggests that the similar pattern seen in most countries suggests that differences in monetary policy regime were not crucial in this particular case:

The most important thing to remember about the lessons learned from the post-pandemic inflation surge is that it has been very similar across countries, implementation and policy strategy to the other. So for single-mandate inflation targets, like the Bank of England, inflation was too high. For single-mandate inflation targets, for the Eurozone, inflation was too high.

Inflation was too high in Switzerland. It was too high in Australia. It was too high in Canada. Furthermore, with the exception of the SNB and the Norwegian Central Bank, all other advanced inflation-targeting countries have also chosen to lag behind, in the sense that they have only started raising rates only when their country’s underlying inflation has significantly exceeded the target. . It was therefore a question of initial conditions – inflation had been too low for a decade – and of the scale and complexity of the shocks, because they affected both supply and demand, which led the banks power plants to do very similar things and to have very similar takeoffs. , a very similar inflation story, and now a very similar disinflation.

So I think and I predict that over time, researchers will look back on this period and not think that it revealed much about inflation targeting versus flexible targeting of average inflation versus single mandate versus dual mandate. They believe this will reveal something about the initial conditions, as well as the magnitude and complexity of the shocks.

I would say that the trend observed nationally suggests that some differences between political systems are more important than others. Take for example the case of China, which has seen its inflation rate fall to levels lower than even those of Japan, even slightly below zero. Why could this have happened?

It should be noted that the Japanese currency has recently depreciated very sharply against the US dollar, while the Chinese currency has depreciated only very modestly. A few experts suggested that China was reluctant to allow a sharp depreciation of its currency, for fear it would trigger a protectionist response in the United States. Whatever the reason, China appears to have fallen into an excessively restrictive monetary policy because it is reluctant to allow a dramatic fall in the exchange value of its currency.

This is another example of the situation in which the approach to the price of silver The policy approach can be much more powerful than the interest rate approach, a point I made in my recent book. Once China decided not to allow a sharp fall in its nominal exchange rate, it could only achieve an equilibrium real exchange rate by allowing deflation in the price level. A similar phenomenon occurred in Argentina in the late 1990s, when a fixed exchange rate combined with a strong U.S. dollar led to price deflation.

PS. Nothing in Clarida’s interview made me optimistic about the Fed’s upcoming policy review. It seems clear to me that, at a minimum, the average inflation targeting regime needs to be symmetrical, but I don’t see Fed officials advocating this type of change. I hope I’m wrong, but I expect the same thing: a political “rule” that allows far too much discretion.