Every public policy has its own set of externalities and unintended consequences. Moreover, because policy sits at the intersection of competing interests, outcomes can often approach a zero-sum game, whether or not that was the initial goal of policymakers. Simply put, someone wins while someone loses; there is always a cost. In my previous message, we finished by taking a quick look at some of the social costs of drug prohibition, such as increased violence, property crimes, and increased incidence of overdose deaths. In this article, we’ll take a closer look at the (sometimes hidden) costs imposed by the War on Drugs™.

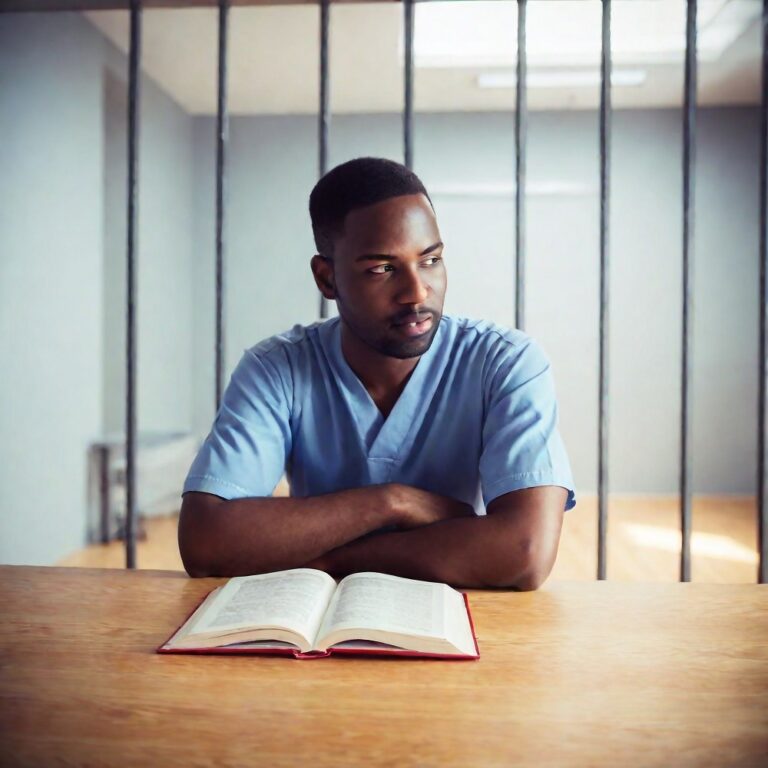

The astonishing growth of the prison-industrial complex

Despite making up approximately 4.23% of the world’s population, the United States accounts for nearly a quarter of the world’s prison population. At any given time, 1.9 million people are unwitting guests of federal, state and local prisons, a per capita rate of 565 per 100,000 inhabitants. (Note: As a result of COVID, many states chose to release prisoners early due to health and staffing concerns. This resulted in a temporary 16% drop in the incarceration rate). For comparison, China, which has four times the population of the United States and is known for its repressive regime, has 1.7 million people incarcerated in its prison system, a per capita rate of just 119 individuals per thousand . According to the Federal Department of Prisons, approximately 44% of inmates in federal correctional facilities are held there for drug offenses.. That figure drops to about 25 percent for state and local facilities, a share of the prison population exceeded only by those incarcerated for violent offenses.

By creating an entirely new class of criminals, drug policy has generated an ever-increasing need for space to house these inmates. While Richard Nixon-era drug policy tended toward treatment rather than incarceration (which is not to say that Nixon didn’t want incarceration; He did, at least from some segments of society), Reagan’s Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984 established mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenders (and civil asset forfeiture, another social cost that deserves discussion). This, of course, precipitated an increase in the prison population, but it was the Clinton administration’s Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 that revived the prison construction industry. prisons. Not only did this law impose a minimum sentence of 25 years for individuals convicted of a crime for the third time, he set aside $97 billion for the construction of new prisons. State and local governments took advantage of this funding, and while adding their own funds, 544 correctional facilities were built between 1990 and 2015, an average every 10 days.

The straw that stirs this harmful drink is the Prison Industry Improvement Certification Program (PIECP). While the Thirteenth Amendment allowed prisoners to be used as a source of cheap labor, this use was limited to use by individual states, as it was illegal to transport prisoner-made goods across state borders or to use prison labor for private entities. When IPECP was approved by Congress in 1979, these restrictions on prison labor were lifted, introducing perverse incentives into the criminal justice system in the name of profit. With Reagan’s ACT requiring new spaces for the influx of drug offenders, businesses and political leaders not only began entering into contracts to build and operate new facilities, but officials also began negotiating with the private sector for opportunities to monetize and profit from prison labor (Chang & Thompkins, 2002). In essence, prisons have transformed from a nominally rehabilitative and functionally punitive institution to a source of profit. Thus was born the prison-industrial complex.

Much of the literature on this strange paradigm focuses on the rise of private prisons, but while these facilities are problematic, they only house 8% of incarcerated people. The pressing problem is that the profit motive that exists in private, for-profit correctional facilities also exists in state and local government-funded facilities. This is reflected in the fact that large institutional investors such as Merrill/BofA Securities purchase prison construction bonds to the tune of more than $2.3 billion per year (Cummings, 2012). They are willing to finance the construction of private and public prisons because they guarantee generous returns. This return on investment is ensured by the low wages paid to inmates, both those employed in maintaining the facilities and those working for private industry.

Estimates suggest that prison labor is responsible for more than $2 billion in goods and services, while prisoners earn pennies on the dollar; the average wage is between 13 and 52 cents per hour. Additionally, correctional facilities earn additional revenue by charging inmates for items such as room and board, court fees, and necessities such as toiletries. These chargebacks can represent up to 80% or more of the inmate’s exorbitant salary, and some even leave their incarceration in a monetary deficit. Prisoners who are fortunate enough to work for private employers under the PIECP program receive a higher salary which must be commensurate with prevailing local wages. That’s less than 6% of inmates, and their chargebacks tend to be even higher.

The irony of this situation is that the PIECP was intended to strengthen the rehabilitative function of prison labor by imparting skills to prisoners that would be valued in the market after their release. A confluence of interests, politicians wanting to appear tough on crime during election time, police departments getting better funding and equipment to focus on drug arrests, prisons that benefit directly from contract labor and private interests wishing to exploit the many opportunities. available to them through low-cost financing, construction, and labor, have all conspired to turn the whole thing into a cottage industry of perverse incentives.

In my next post, we will continue the militarization of the police.

Tarnell Brown is an economist and public policy analyst based in Atlanta.