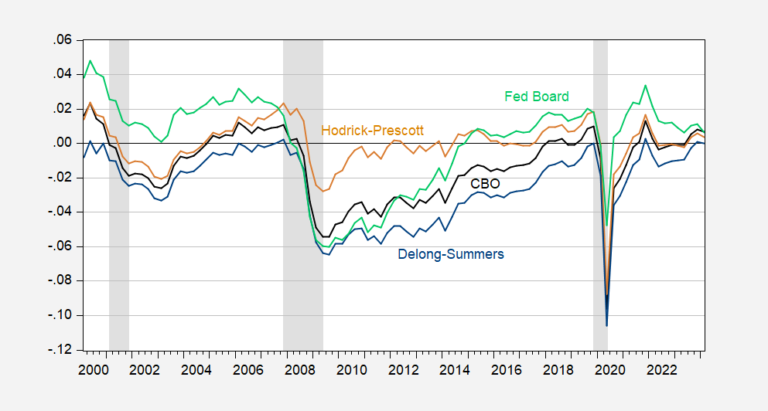

This involves rethinking the production gap and the concept of trend-cycle decomposition in tomorrow’s macroeconomic policy. Here is a picture of the CBO output gap, using two statistical filters (Hodrick-Prescott and Fleischman-Roberts/Fed Board), and the Delong and Summers (BPEA 1988) model.

Figure 1: Output gap calculated using CBO potential GDP (black), HP filter applied to the period 1960-2024 (beige), Fleischman and Roberts/Fed Board double-sided filter (light green) and the approach pseudo-DeLong-Summers (1988) (blue). The NBER has defined the peak to trough dates of the recession in gray. Source: BEA 2024Q1 advance, CBO (February), Atlanta Fed Taylor Rule utility data accessed 04/26/2024, NBER and author’s calculations.

It is worth noting that the HP filter produces implausibly small (in absolute terms) output gaps following the Great Recession. On the other hand, both bandpass filters like the Baxter King filter or the Hamilton filter which relies on a regression method to extract the trend, indicate sharp declines and jumps in the trend associated with the recession of Covid-19 (not shown).

The CBO’s “production function” approach to estimating the trend is not as affected by the Covid-19 shock and is more consistent with an economic interpretation. However, it has been subject to substantial variation as productivity estimates have changed; and more recently, because immigration affected the projected labor stock.

Jim Hamilton has a different interpretation of potential GDP which is based on a differentiated adequacy (by specialization) of supply and demand for labor and capital. Changes in the composition of demand relative to supply could then lead to a slowdown. However, I do not have a time series of this interpretation of the potential.

Another interpretation of potential GDP is that we cannot take the usual breakdown of trends and cycles for granted. Blanchard, Cerutti and Summers (2015) argue that the trend and the cycle could be correlated. They observe that trend GDP growth has generally declined following recessions. This is not a natural outcome in the standard view of business cycles. For example, in the CBO production function approach, a recession should only affect trend growth to the extent that reduced capital investment and worker discouragement could reduce potential (presumably to a small extent). . In a cross-national analysis, they find that this is not the case.

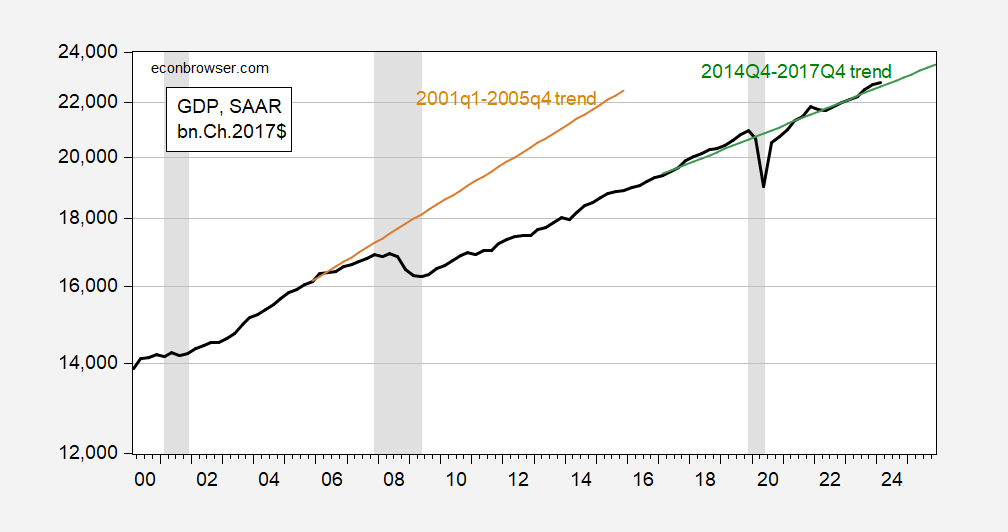

I’ve updated the Blancard-Cerutti-Summers chart for the United States, to further include the post-Great Recession period and the post-2020 recovery.

Figure 2: GDP (bold black), linear trend 2001-2005 (beige) and linear trend 2014-17 (green), all in billions of Ch2017$ on a logarithmic scale. The NBER has defined the peak to trough dates of the recession in gray. Source: BEA 2024Q1 advance release, NBER and author’s calculations.

The BCS approach indicates a significant decline in the mean and trend. The recession could have occurred because agents perceived an anticipated decline in the components of potential GDP (TFP, capital and labor stocks) as traditionally conceived, or because of the scars from a damaged financial system, as well. than a prolonged period of stagnation in demand (due, for example). to 50 Little Hoovers, including Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker).

Interestingly, the 2020 crisis apparently did not have a major impact on average or trend GDP. This suggests that either the 2020 recession was not caused by a quiet decline in expectations about the components of potential GDP, or that scarring was avoided through rapid and forceful fiscal and monetary policies.