Following October 7, 2023 Hamas attacksIsrael’s military operations in Gaza and their humanitarian consequences brought the issue of trade sanctions against Israel into public debate. As of July 2024, the Israeli offensive had resulted in the deaths of more than 37,000 Palestinians. This number could reach more than 186,000 Considering indirect deaths due to, among other things, the destruction of health infrastructure or water and food shortages, 70% of Gaza’s homes have been destroyed and 80% of the population has been displaced. In response, Turkey has suspended trade while other countries, including Belgium, Canada, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands and Spain, have suspended trade. have decided to stop the arms tradeIn Europe, the governments of Belgium, Ireland and Spain have publicly advocated for the implementation of trade sanctions. The issue was also raised in the Foreign Affairs Council of the European Union.

Economic sanctions have become a major tool of contemporary foreign policy. As of 2023, the UN manages 14 ongoing sanctions, while the United States has imposed more than 25 since the early 2000s. Research on their effectiveness suggests that economic sanctions tend to be most effective when they impose substantial economic costs on the targeted economy, are multilateral and led by international institutions, aim at moderate policy changes rather than ambitious goals, target allies rather than adversaries, and are directed against democratic regimes.

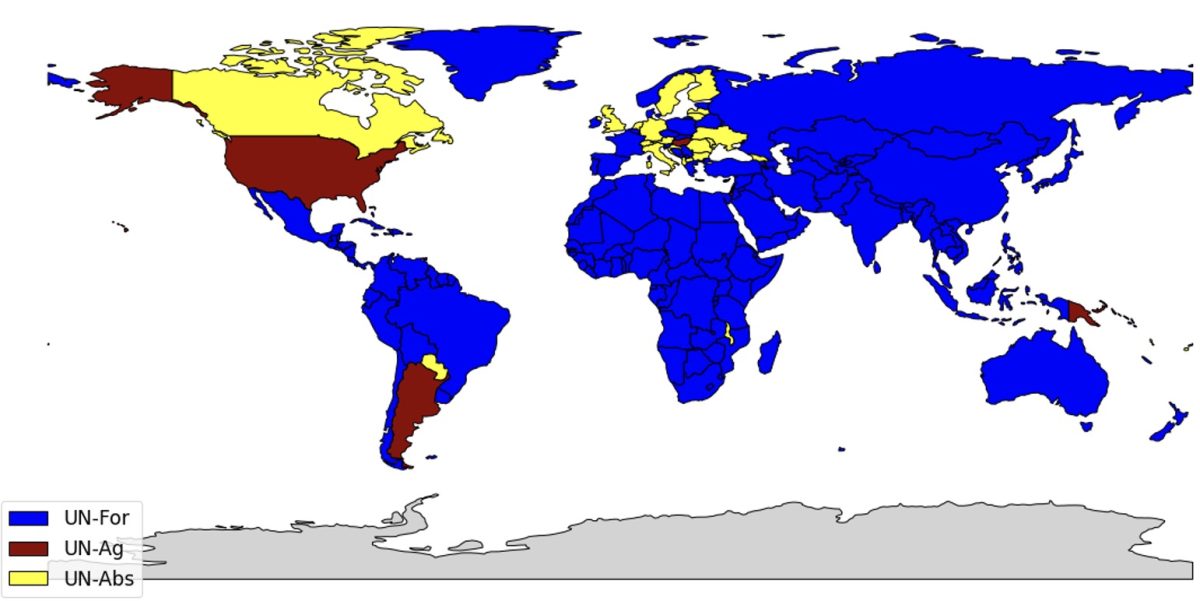

In this analysis, I use a multi-country, multi-sector trade model to examine the effects of tariff sanctions on Israel. The model is based on De Souza et al (2024), Caliendo and Parro (2015) And Ossa (2014)Firms in each country competitively produce tradable goods in different sectors that are used both for final consumption and as factors of production alongside labor and intermediate inputs. Trade is subject to iceberg costs as well as import and export tariffs set by governments. I calibrate the model using the OECD Inter-country Input-Output Tablea dataset that describes the interdependencies between 45 economic sectors and 76 countries. I classify countries into 4 groups based on their vote on the resolution (A/ES-10/L.30/Rev.1) for the admission of Palestine to the UN: Israel, the countries that voted against the resolution (abbreviated as “UN-Ag”, 9 countries including the United States, Argentina, Hungary), the countries that voted for the resolution (abbreviated as “UN-For”, 143 countries including China, France, Japan), and the countries that abstained (abbreviated as “UN-Abs”, 25 countries including the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Canada). Figure 1 shows a map of the countries according to their different votes.

I assume that the countries imposing sanctions are those in the “UN-For” group. I acknowledge that this assumption involves a significant degree of arbitrariness. The question of which countries are most likely to impose sanctions is beyond the scope of this analysis. Rather, the goal here is to assess the effects of such sanctions. I have compared this group to other hypothetical coalitions of countries imposing sanctions: the European Union, the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa), and the United States. Finally, although I focus here on the economic consequences of import and export tariffs, economic sanctions can also be implemented through a variety of other means, including asset freezes, financial market sanctions, or entry restrictions on key government officials and business leaders.

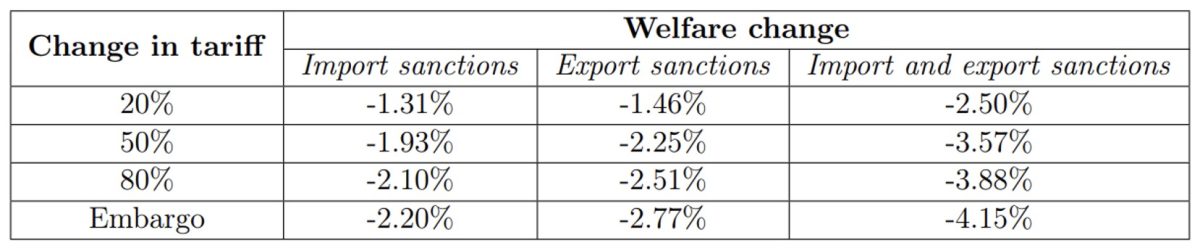

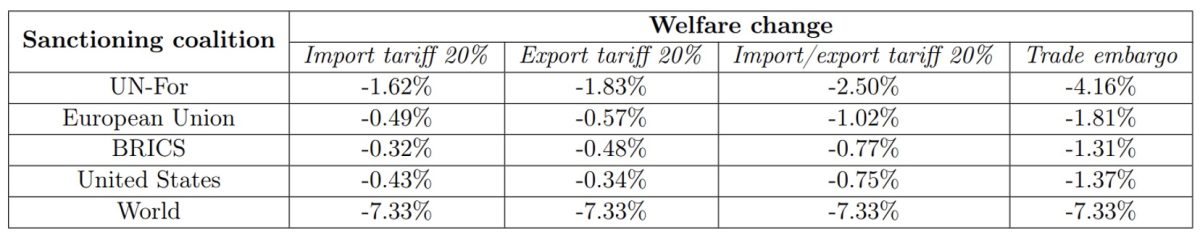

The results, presented in Table 1, show that export tariffs would have a slightly larger impact than import tariffs. With a 20% change in import tariffs, Israel’s gross national income (GNI) would decrease by 1.31%, and by up to 2.20% in the case of an import ban. For a 20% change in export tariffs, the decrease would be 1.46%, and by 2.77% in the case of an export ban. When both measures (import and export tariffs) are combined, the decrease ranges from 2.50% (20% tariff) to 4.15% (trade embargo). Finally, in all scenarios, the impact of sanctions on other countries (sanctioning or not) is negligible, around -0.02%. This means that there is no economic compromise regarding the level of customs duties: it is a political choice.

Table 2 compares the results of different coalitions of sanctioning countries. A 20% increase in import and export tariffs by the European Union would reduce Israel’s GNI by 1.02%. The same increase by the BRICS would reduce it by 0.77%, about the same as that of the United States (0.75%). For comparison, the impact of a trade embargo by the EU would be -1.81%, by the BRICS -1.31%, and by the United States -1.37%. At the extreme, if all countries in the world were involved in a trade embargo, the impact would be -7.33%. This shows that the larger the coalition imposing sanctions, the greater the economic impact.

These values are within the range of Neuenkirch and Neumeier (2015)who estimate the impact of “severe” UN sanctions, such as full embargoes imposed by UN member states against a targeted country, to be in the order of -5 to -6% on GDP growth. They are also consistent with the predictions of the Armington model that welfare gains from trade should be at least 1 − λ−1/εwhere λ is 1 minus the import penetration rate and ε is the trade elasticity. Israel’s import penetration rate is 17%, so λ = 0.83, the trade elasticity is about -5, implying that the welfare losses due to the embargo are at least 3.66%.

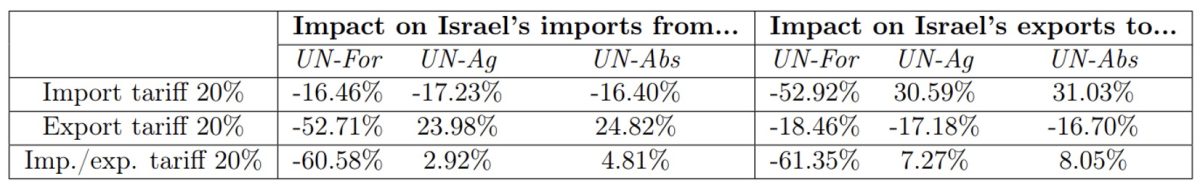

Table 3 shows the effect of sanctions on trade between Israel and other countries. The imposition of a 20% tariff on imports (resp. exports) by UN-For would reduce Israel’s exports to (resp. imports from) these countries by 52.92% (resp. 52.71%). This measure would be partially offset by an increase in Israel’s exports to (resp. imports from) non-sanctioned countries: 30.59% to UN-Ag, 31.03% to UN-Abs (resp. 23.98% for UN-Ag, 24.82% for UN-Abs).

I now study the distribution of the effects of trade sanctions by sector. I assume that countries imposing sanctions impose a 20% increase in import and export tariffs, and that Israel imposes no counter-sanctions. I also assume that there are no sanctions on food and pharmaceutical products.

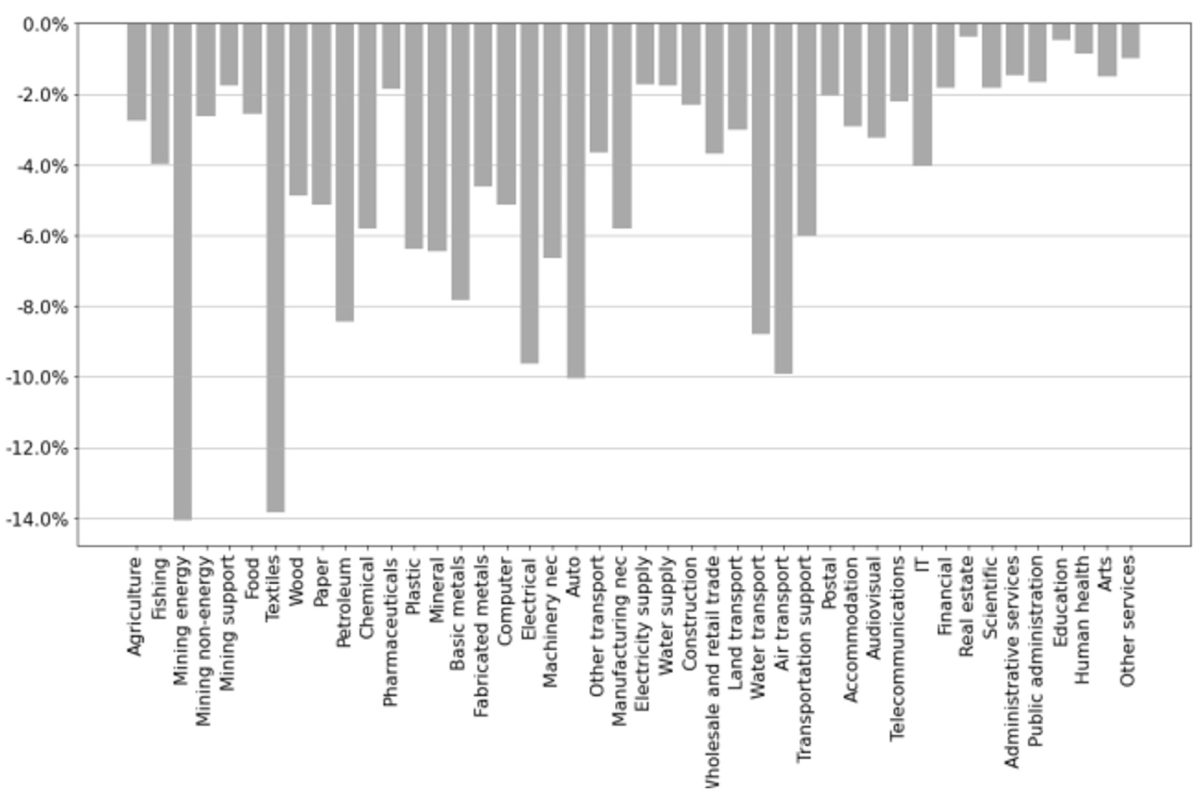

Figure 2 illustrates the evolution of the purchasing power of wages (PPW) across various sectors. It reveals the extent to which the quantity of goods or services that can be purchased with a unit of wages changes in each sector as a result of the sanctions. The sectors experiencing the largest decline in PPW are fossil fuels (-14.07%) and textiles (-13.83%). Refined petroleum (-8.43%) is also particularly affected due to the impact on fossil fuels. Other sectors experiencing significant declines are automobiles (-10.06%), air transport (-9.92%) and electrical equipment (-9.63%). The effects on essential goods, such as food (-2.58%), pharmaceuticals (-1.85%) and electricity (-1.73%), remain moderate.

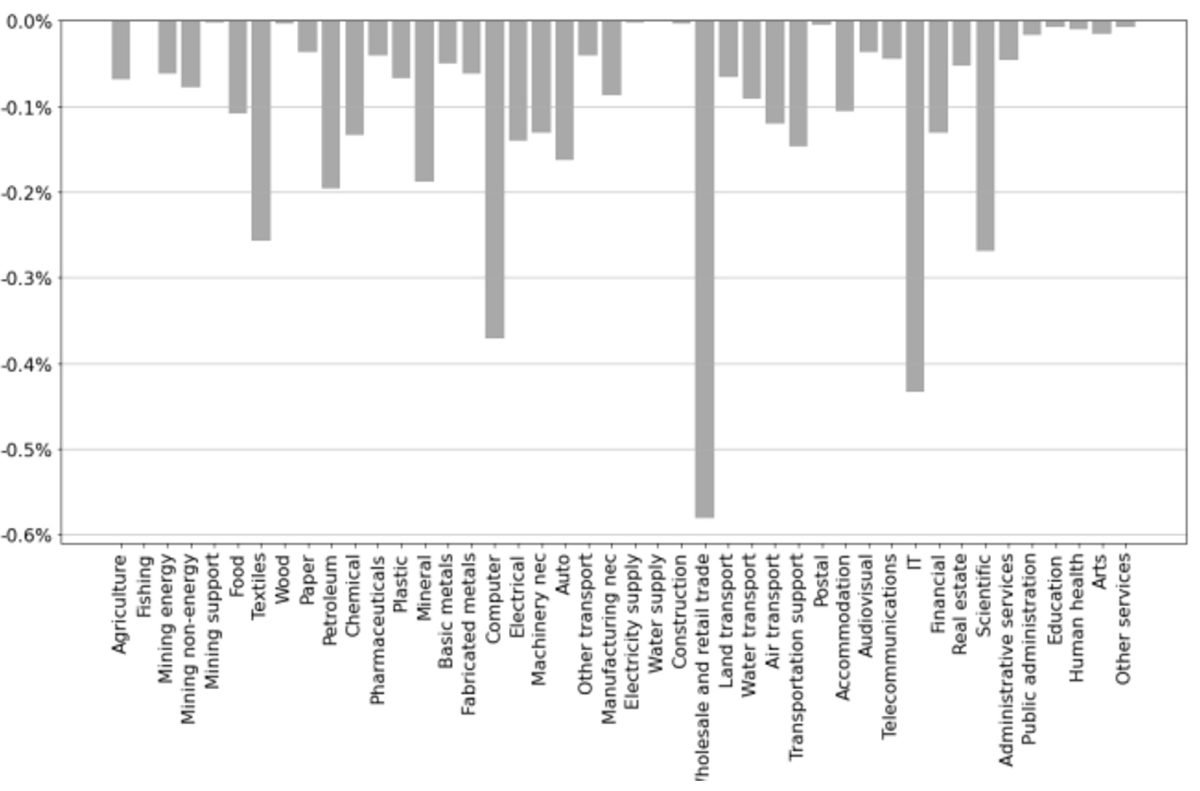

Finally, I look at the sectors that are the most effective targets for sectoral sanctions. Figure 3 shows the change in Israel’s GNI resulting from a trade embargo in each sector. The sectors in which targeted sanctions would be most effective include wholesale and retail trade, information technology (IT), computing, and scientific services. These last three sectors underscore Israel’s reliance on its high-tech economy. In 2022, the high-tech sector accounted for 18.1 percent of Israel’s GDP, an increase of four percentage points from 2012, making it the largest sector in the country’s economy. High-tech also accounted for 48.3 percent of Israel’s exports, a figure that has more than doubled over the past decade.

The results of this study indicate that customs sanctions could have significant effects on Israel’s gross national income. Sanctions are most effective when they involve a large number of sanctioning countries and when they target high-tech products and services.

Tables and figures

Figure 1: Map of countries according to their vote on the resolution (A/ES-10/L.30/Rev.1) for the admission of Palestine as a member state of the UN.

Figure 2: Evolution of the purchasing power of salaries by sector.

Figure 3: Impact of the sectoral trade embargo on GNI by sector.

Table 1: Evolution of Israel’s gross national income following various tariff changes.

Note: Import sanctions are an increase in import tariffs by the coalition imposing the sanctions. Export sanctions are an increase in export tariffs by the coalition imposing the sanctions.

Table 2: Evolution of Israel’s gross national income under different sanctions coalitions.

Table 3: Impact of tariff sanctions on Israeli imports and exports.

Further reading on electronic international relations