PM Images/DigitalVision via Getty Images

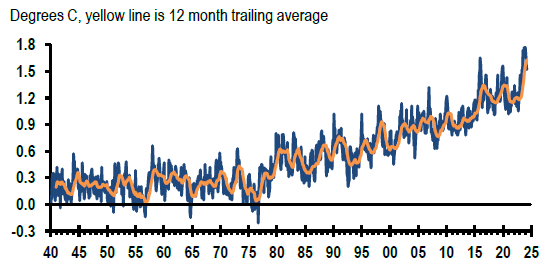

The average temperature on the Earth’s surface in May 2024 was higher than any other May on record, marking the twelfth consecutive such month. According to the European Union Copernicus Service on Climate Change, The temperature of May was 1.52 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial average, while temperatures over the past twelve months have averaged 1.63°C above (Figure 1). Global sea surface temperatures have also set records over the past fourteen months.

Figure 1: Increase in global surface temperature compared to pre-industrial temperatures

JP Morgan

Source: Malcolm Barr (2024), The pushback on policy to limit climate change, in JPMorgan, Global Data Watch, June 21 (with data from Copernicus Climate Change Service).

Take the example of the floods that occurred in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, in April and May 2024. World Weather Attribution The study has already estimated that the The probability of this phenomenon occurring has been more than doubled by climate change, combined with the El Niño phenomenon, the intensity of which has increased by 6 to 9%.

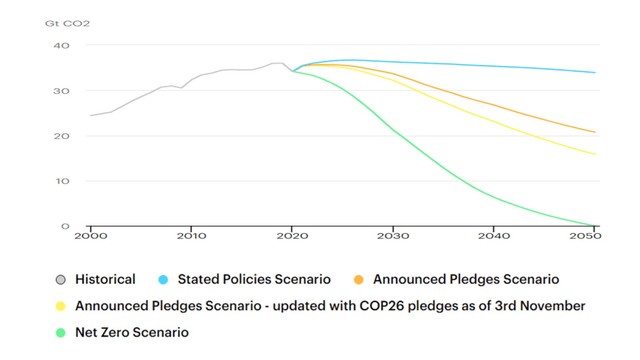

Unsurprisingly, scientists stress that actions taken over the coming decade will be crucial if the world is to meet the 2015 Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting human-caused climate change to less than 2°C, with the hope of not exceeding 1.5°C. Following the COP26 Climate Change Conference in Glasgow in 2021, the International Energy Agency has updated its CO2 emissions scenarios in its CO2 Emissions Report. Global Energy Outlook (IEA, 2021)taking into account the commitments made by countries at the time. Despite a sharper decline in emissions, the world is still far from reaching the dream scenario of net zero emissions by 2050 (Figure 2). Whatever happens in the current decade in terms of emissions will have consequences for climate change in the future (Canuto, 2021).

Figure 2: CO2 emissions scenarios over time, 2000-2050

Source:IEA (2021).

As Malcolm Barr also reported in a JPMorgan Global Data Watch report released on June 21, 2024, the assessment discussed at COP28 in Dubai last year concluded that the world is not on track to meet these goals. There are doubts about whether countries’ nationally determined contributions (NDCs) will reduce global greenhouse gas emissions enough to limit global warming, or whether countries will individually take the necessary steps to implement their individual plans.

There are also doubts about whether financial flows from developed countries to developing economies, promised to help the latter transition to green energy and production and mitigate current climate impacts, will be large enough.

COP30 in 2025 in Belém, Brazil, is expected to deliver a comprehensive new set of NDCs, covering at least the period until 2035. Nothing similar is planned for COP29 in November this year, in Baku, Azerbaijan. The evidence that COPs contribute to giving countries more effective commitments to limit climate change will be demonstrated if countries reduce their emissions much more quickly and if more resources are secured for developing countries.

Unfortunately, recent political developments have shown that efforts to limit climate change face risks and delays.

For example, popular support is growing for right-wing politicians in Europe. Although the European Union (EU) has long positioned itself as a leader in the fight against climate change, it is increasingly common for its right-wing parties to question the speed and necessity of its environmental policy. This has already led to the dilution of parts of the EU’s European Green Deal package.

This trend is not uniform across the region, considering for example that in the UK, polls suggest that the Conservative Party, which has diluted its climate commitments, is likely to lose the election to the Labour Party, which is more committed to carbon neutrality. On the other hand, the gains of the political right in the recent European parliamentary elections, as well as, according to current polls, its likely rise in the French parliamentary elections in July, challenge the existing consensus around environmental policy.

In the United States, the possibility of Trump returning to the presidency does not bode well for the carbon emissions reduction agenda. During his previous term, Trump withdrew from the Paris Agreement, a decision reversed by his successor Biden. Trump’s skepticism about climate change was evident during his first term, but the candidate nonetheless referenced his disagreement with Democrats’ commitment to U.S. climate policy.

Trade tensions over electric vehicles (EVs) are also not helping matters. China has prioritized industries related to the green transition as part of its multi-year strategic policy, in order to meet its structural challenges of growth. It has acquired market leadership positions in various related sectors including batteries and electric vehicles.

The EU recently announced tariffs on imports of electric vehicles from Chinese manufacturers, arguing that they have benefited from unfair state support compared to EU producers. Inflation Reduction Act The United States has subsidies and incentives for the green transition mainly linked to value added in the United States. Goals to ensure that jobs and activities within their own borders are prioritized as the green transition occurs makes this transition more costly and likely less effective.

Bottom line: the evidence that the damage caused by climate change is already here and will get worse is irrefutable. The situation will only get worse if the world fails to reduce its carbon emissions – which will depend on countries establishing and implementing appropriate Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). Recent political developments in countries with significant influence on this trajectory do not appear promising. We can only hope that this development does not lead to more serious consequences for the environment.“The path to decarbonization”.

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, DC, is a former Vice President and former Executive Director of the World Bank, a former Executive Director of the International Monetary Fund, and a former Vice President of the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former Vice Minister of International Affairs in Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former Professor of Economics at the University of São Paulo and the University of Campinas, Brazil. He is currently a Senior Researcher at the Policy Center for the New South, Professor of International Affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs – George Washington University, a non-resident principal investigator at Brookings Institution, A affiliated professor at UM6P and principal at Center for Macroeconomics and Development